How mandatory electronic conspicuity could accelerate Canada’s drone industry

By Scott Simmie

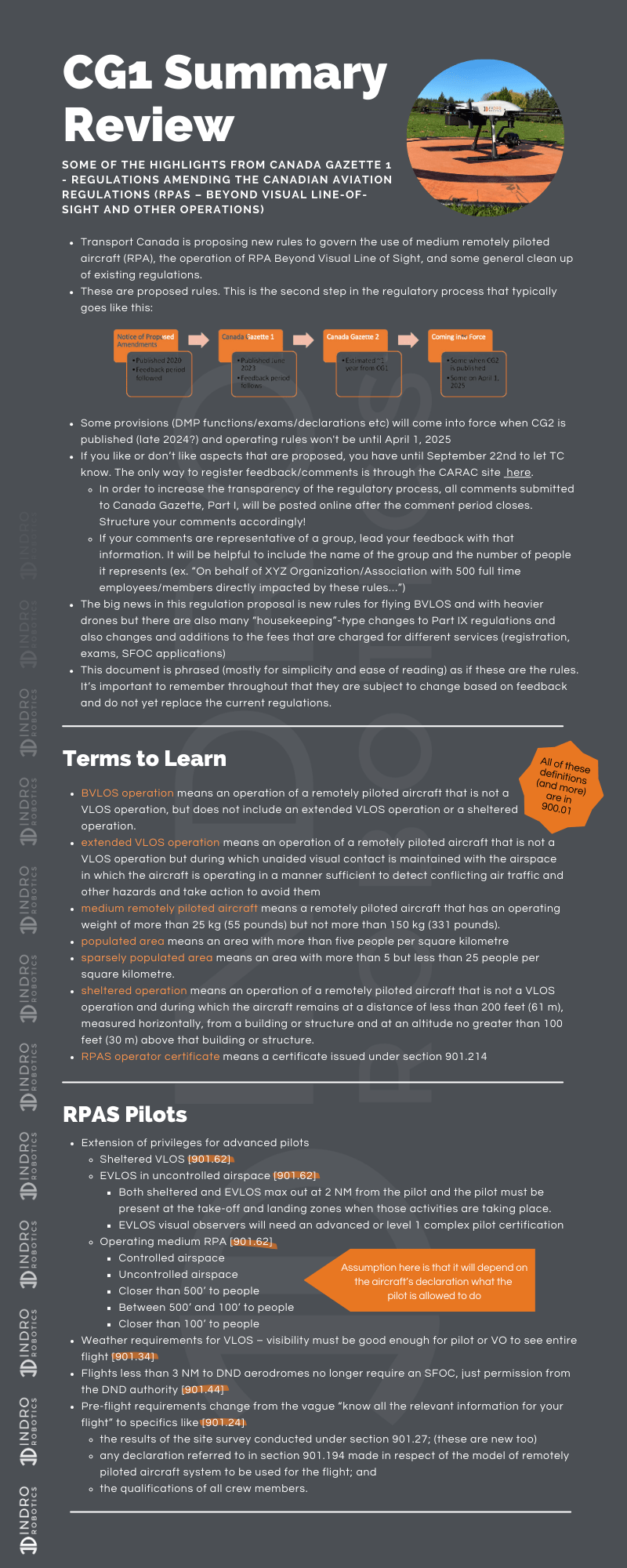

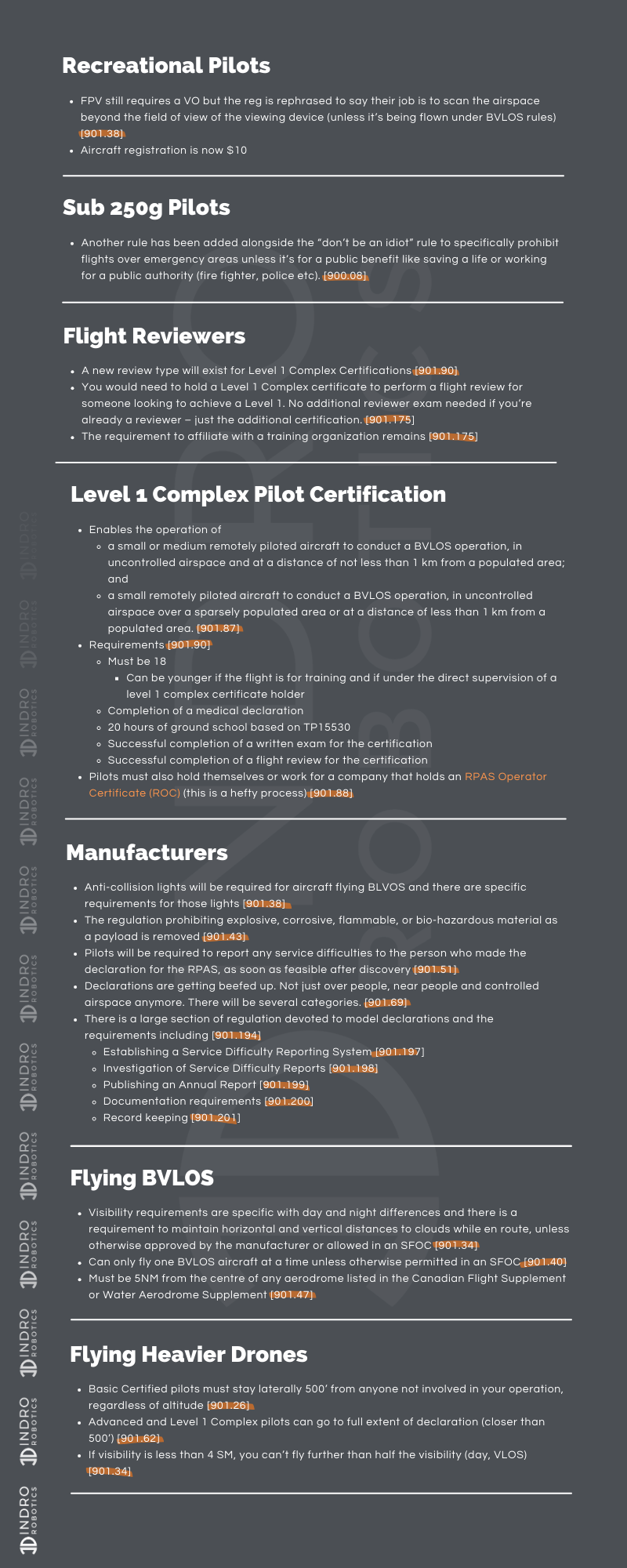

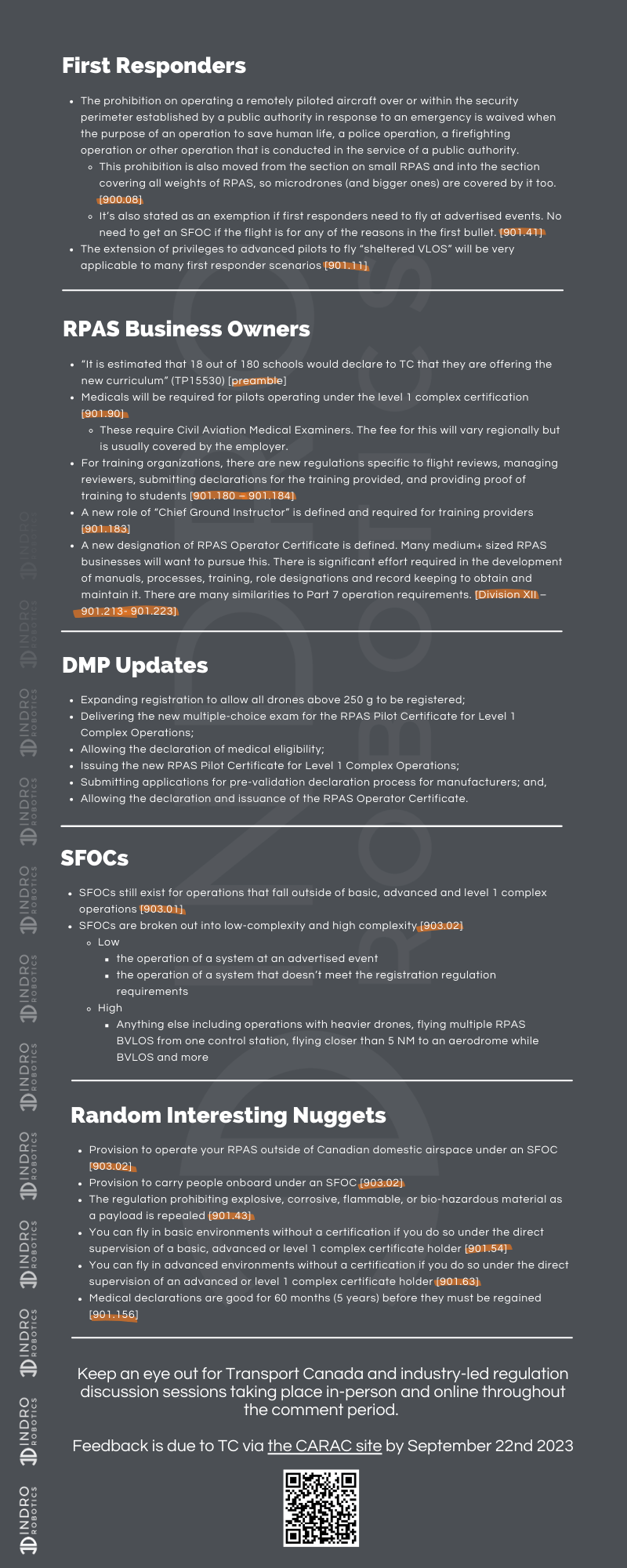

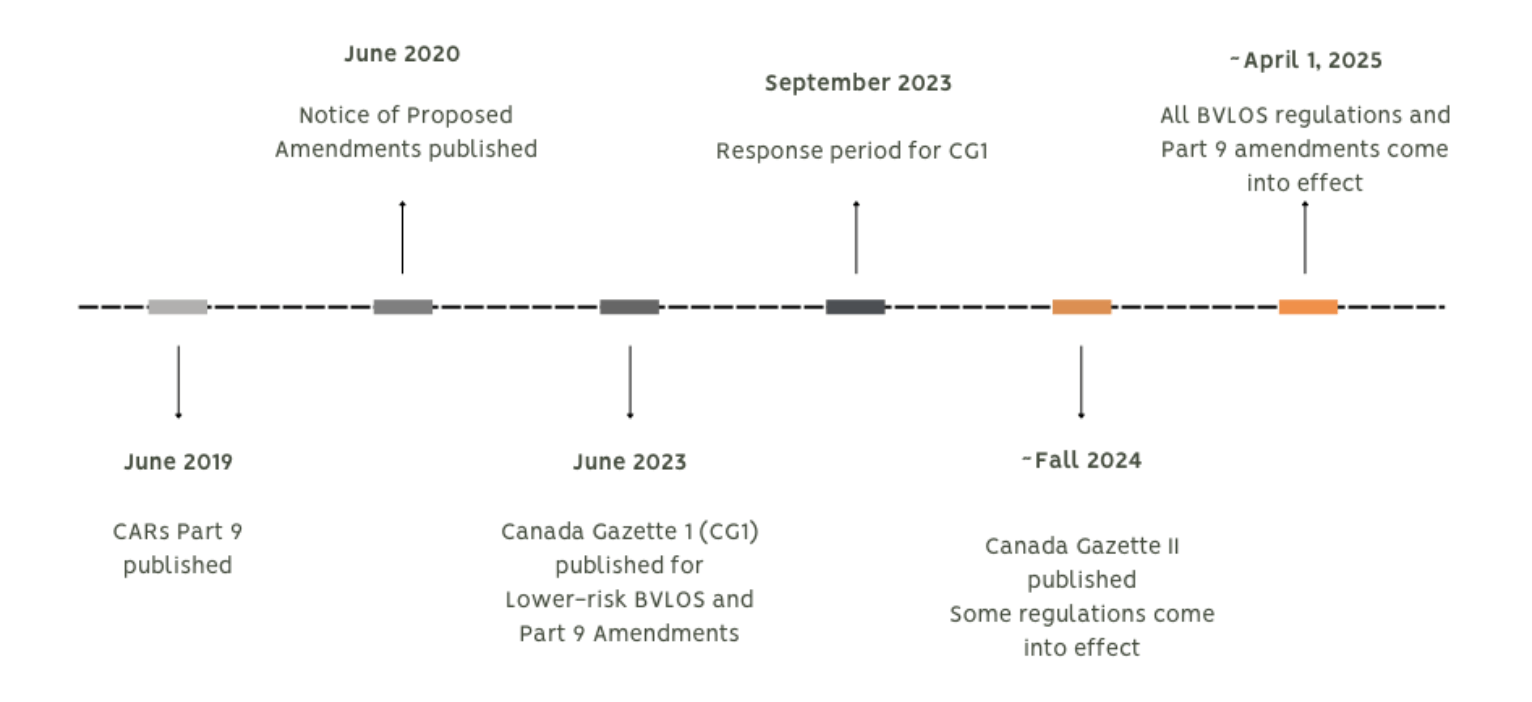

New Transport Canada RPAS regulations go into effect November 4, 2025.

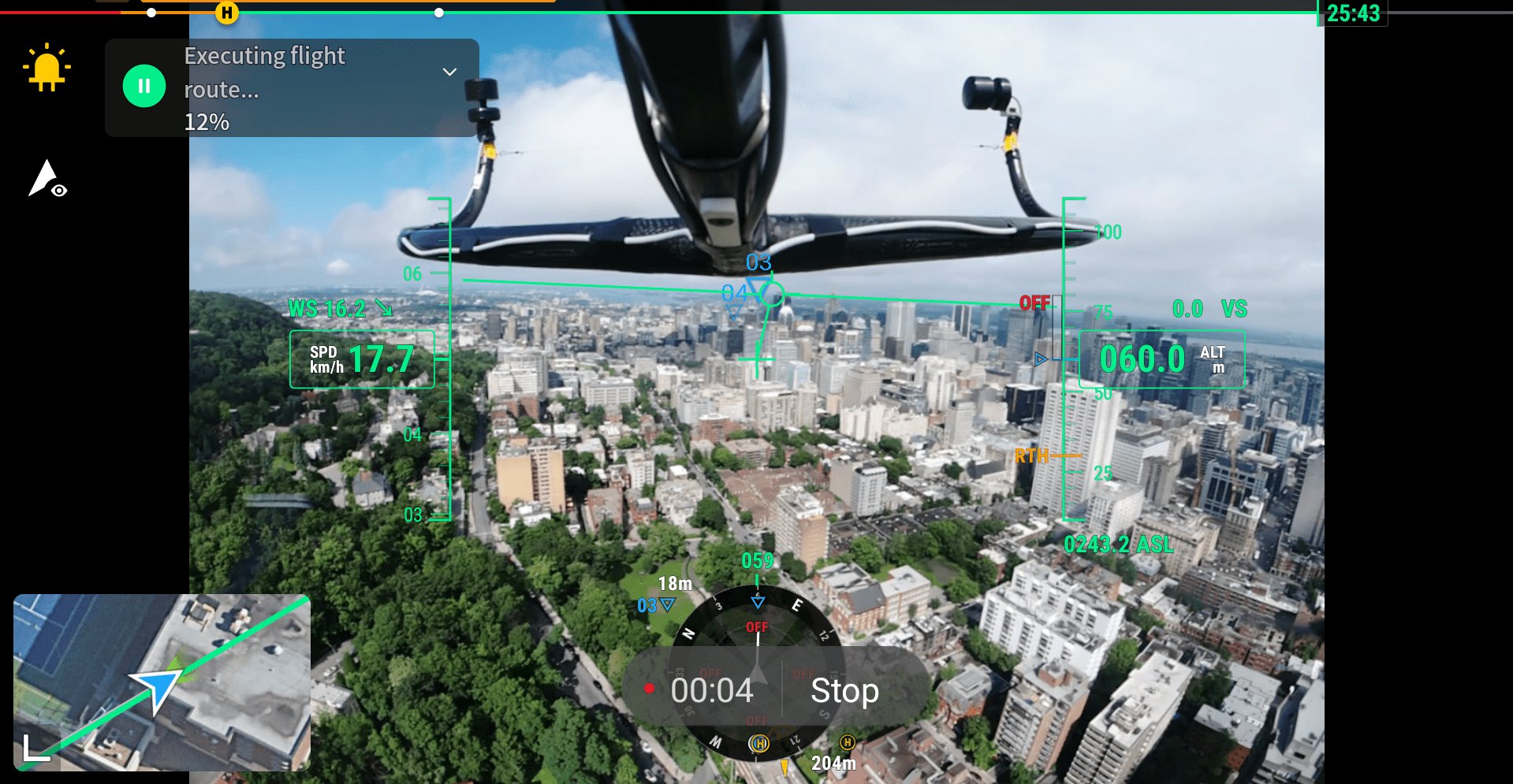

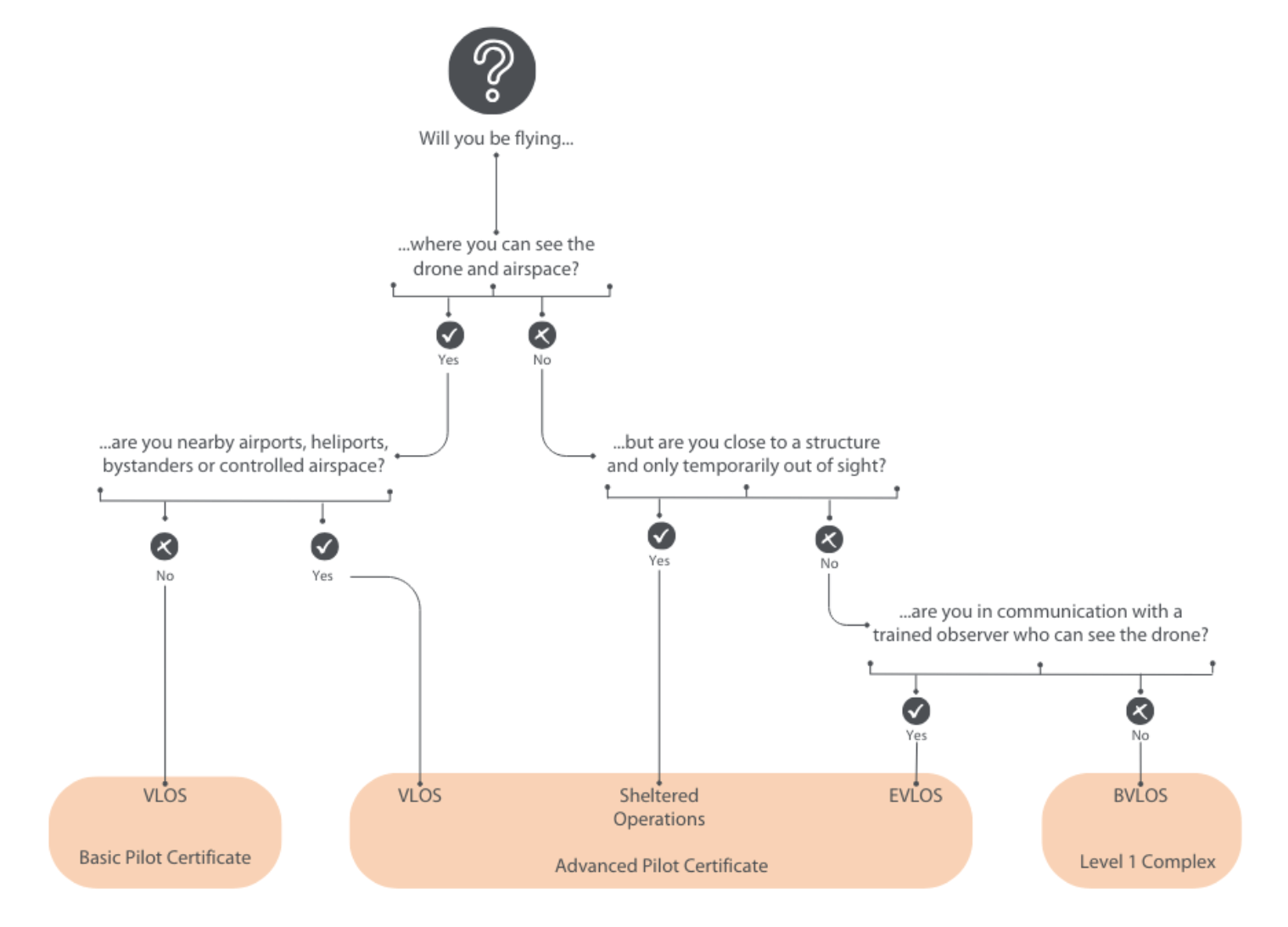

Among many coming changes, the industry is most excited about the prospect of enabling routine, low-risk BVLOS flight for those with the new Pilot Certificate: Level 1 Complex Operations (plus an organization or point person – an Accountable Executive – holding an RPAS Operator Certificate). The RPOC holder accepts overall responsibility for safe operations, including maintenance, training etc. In addition, the drone must meet TC’s safety requirements for Level 1 Complex Operations.

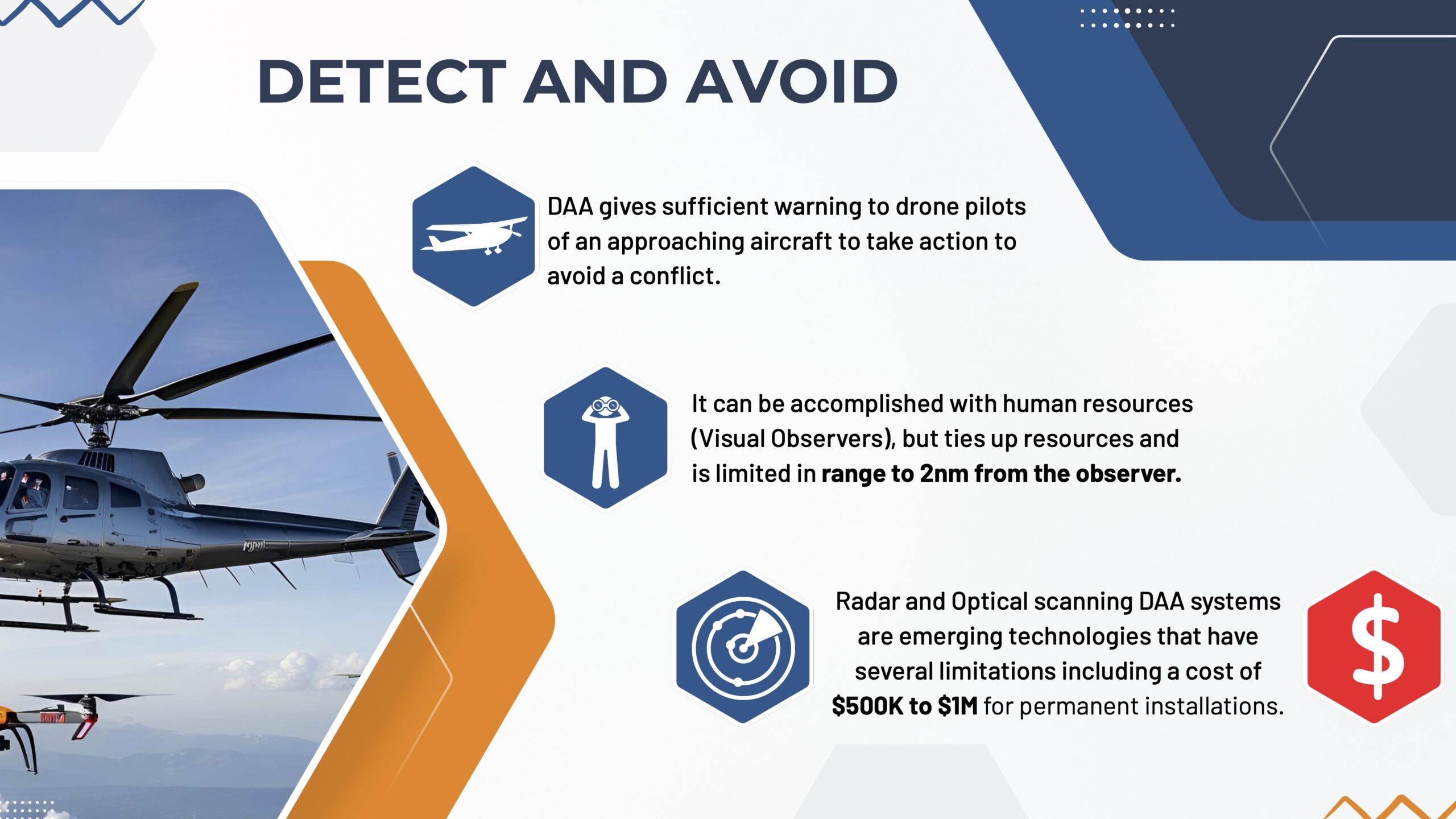

But to fly BVLOS, the regulations require some sort of Detect and Avoid (DAA) system to avoid conflict with traditional low-flying aircraft. TC has provided a standard for vision-based DAA, but it has limitations including a max distance of 4 NM. For longer range BVLOS missions (and there are many applications) or other scenarios that don’t align with the standard, the operation must use a technology-based DAA solution.

For an industry scrambling to take on routine, low-risk BVLOS operations, that’s a bit of a stumbling block. The cost of DAA systems (including ground-based radar) is prohibitive. And that’s why a recent LinkedIn post by Brian Fentiman, CEO of BlueForce UAV Consulting (and InDro’s Law Enforcement Division Consultant) recently caught our attention.

“Canada’s drone industry is ready for BVLOS, but one major barrier remains: affordable Detect and Avoid (DAA) solutions,” he wrote. “Most DAA systems cost over $100k and can run into the millions. That’s not scalable.”

InDro’s Training and Regulatory Specialist, Kate Klassen, agrees, saying “It might be the first time the regulations have been ahead of the technology.”

Below: A look at the issue

ELECTRONIC CONSPICUITY

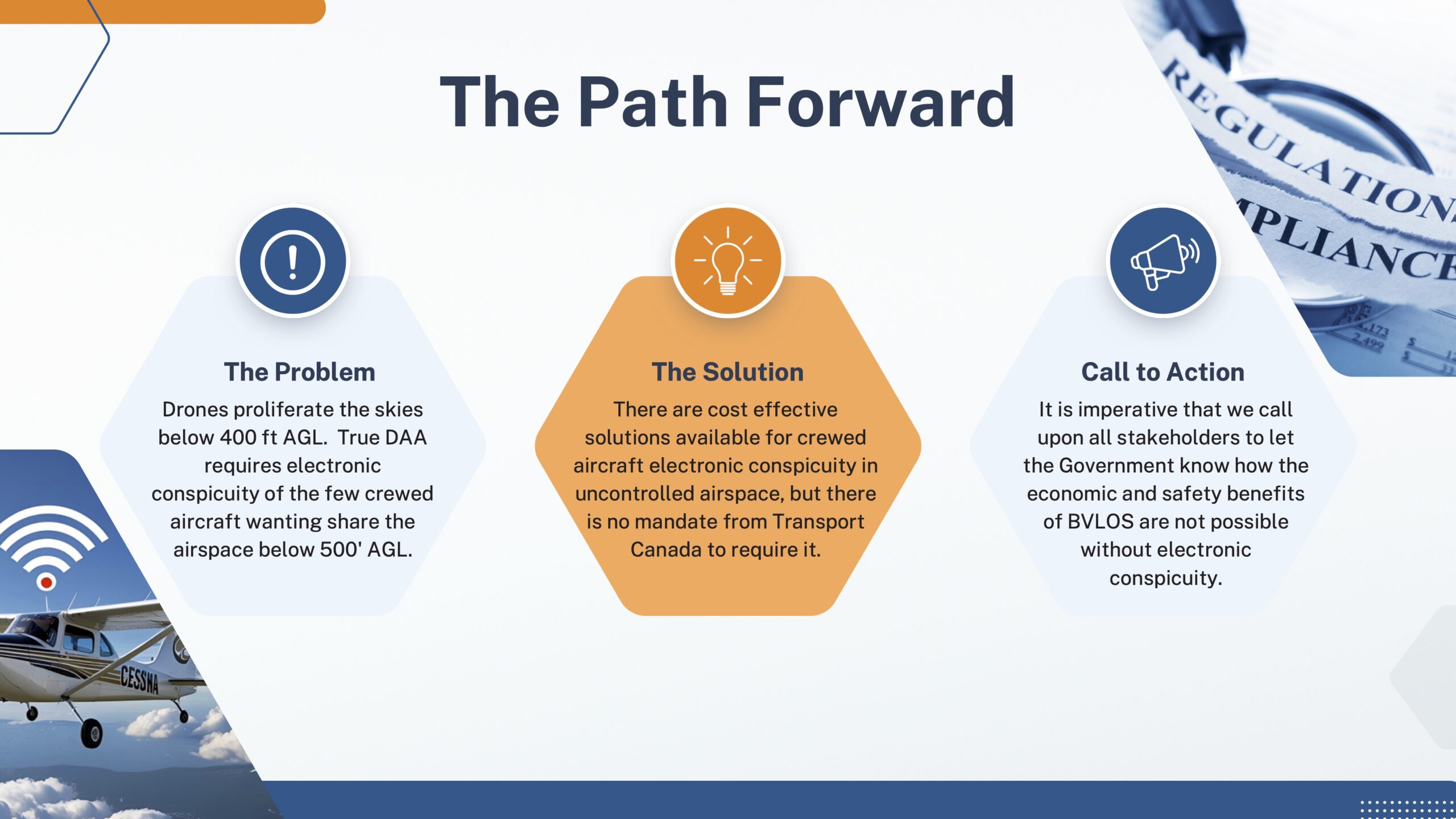

A far simpler and more cost-effective solution, argue many, would be a mandatory requirement for all crewed aircraft flying at lower altitudes to be equipped with an electronic system that constantly broadcasts information about its position and altitude. This generally means Automatic Dependent Surveillance – Broadcast Out, or ADS-B Out. It’s a vastly more affordable path to avoiding conflict between RPAS and low-flying aircraft, and the cost for RPAS operators for technology to detect these signals is inexpensive, accessible, and available.

“The answer lies in Electronic Conspicuity (EC), low-cost ADS-B Out broadcast by crewed aircraft that lets RPAS operators safely detect and avoid traffic,” writes Fentiman. “The US, Australia, the UK, and New Zealand are already doing this. Canada must catch up.”

Fentiman argues such a mandate would quickly open the skies to much-needed RPAS services, including:

- Search and Rescue

- Energy Corridor Inspection

- Emergency Response

- Infrastructure Monitoring

NAV CANADA mandated the use of this technology by traditional aviation flying in Class A Domestic Airspace in 2019, expanding it to include Class B in August of 2023. ADS-B is currently not required in uncontrolled airspace. There will be no further changes for some time to come.

“The implementation of any subsequent Canadian ADS-B mandate in Class C, Class D or Class E airspace will occur no sooner than 2028, pending further assessment and engagement with stakeholders,” says NAV CANADA.

That’s part of the reason why the RPAS industry believes it’s critical to address this issue as soon as possible.

“We don’t have a good RPAS-based solution for Detect And Avoid,” explains Klassen. “And size, weight and power restrictions are a challenging problem, which makes it hard to execute BVLOS missions under these regulations. That’s where Electronic Conspicuity comes in. If we expand the NAV CANADA mandate for ADS-B Out…then the only thing we need on the drone is a system to detect those signals.”

PETITION

With the lack of an approved and affordable DAA system for drones themselves, many in the RPAS industry believe the simplest and most expedient solution is a broader mandate for ADS-B Out on all aircraft that fly below 500′. And so multiple industry partners (including the Aerial Evolution Association of Canada) have come together to create a petition to Transport Canada “to implement a nation-wide requirement for Electronic Conspicuity systems on all low-flying crewed aircraft that share airspace below 500 feet AGL with drones.”

“It’s time to unlock safe and economical BVLOS drone operations in Canada,” writes Fentiman. “A national EC (Electronic Conspicuity) mandate would make Canada safer for both drones and general aviation.”

You’ll find Brian’s full LinkedIn post below – feel free to repost – and you can find a link to the petition here.

INDRO’S TAKE

Like many in the industry, InDro embraces the coming regulations. But we share the belief that the lack of an affordable and approved DAA system will impinge RPAS operators during what should be a period of rapid expansion into routine, low-risk BVLOS flight. That’s why InDro is one of the partners pushing forward this petition.

“Mandating Electronic Conspicuity for all crewed aircraft that share airspace with drones is a logical, practical and cost-effective solution that has the benefit of enhancing safety for traditional aviation, too” says InDro’s Kate Klassen.

Once again, you can sign the petition here. And please spread the word.