InDro’s Dr. Eric Saczuk: The Indiana Jones of Drones

By Scott Simmie

He’s a Fellow International of The Explorers Club – the storied New York-based organization that since 1904 has only accepted members who have travelled to far-flung places (including the moon) in scientific pursuits. He owns a beloved 1989 Volkswagen Westfalia that’s served as his home for academic research and family camping trips. He holds a PhD and sports a prominent and highly meaningful tattoo on his left arm. And, as InDro’s Head of Flight Ops, has flown complex drone missions on six continents – and counting.

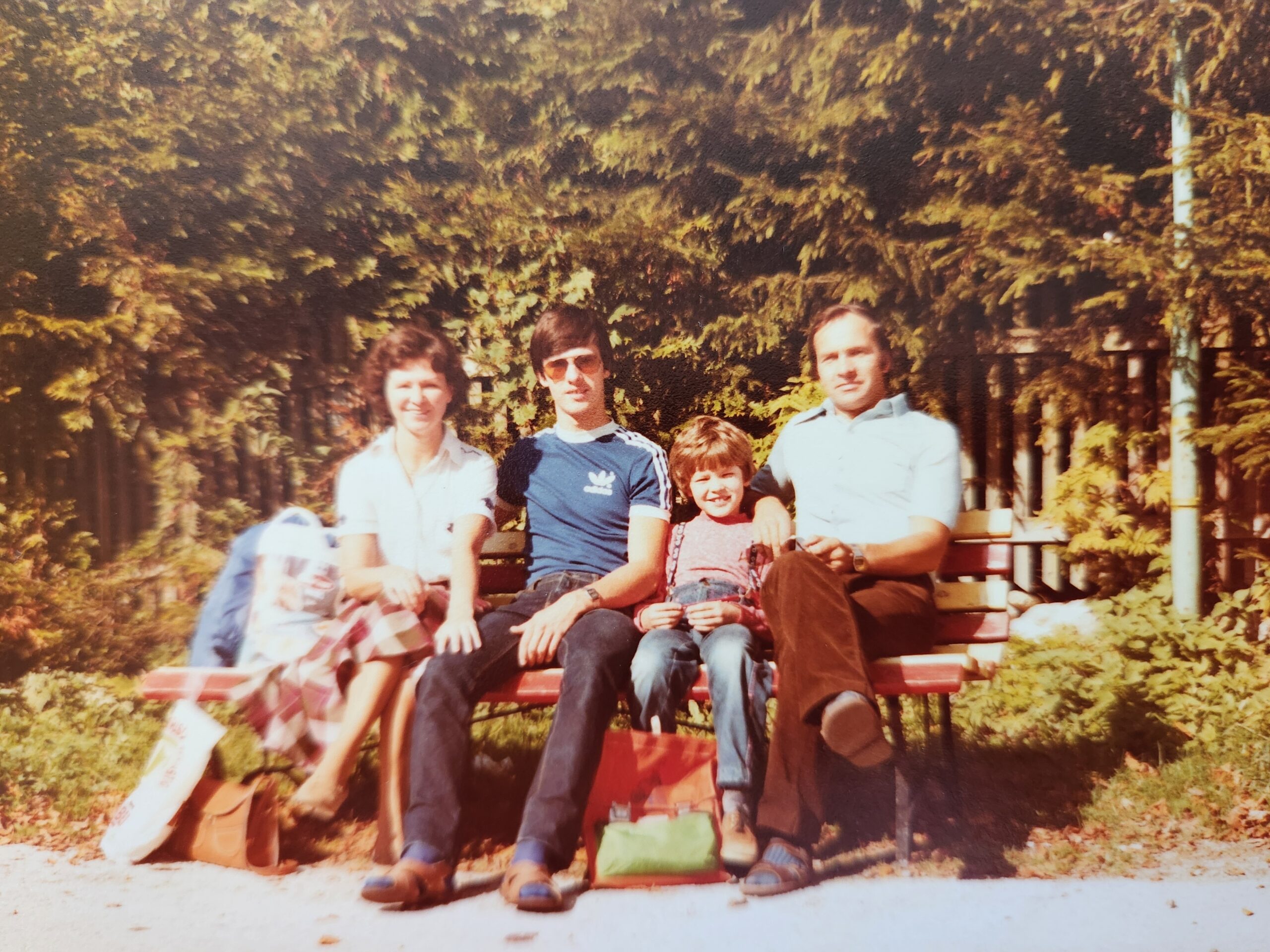

As you might have guessed after reading that, Dr. Eric Saczuk has quite the backstory – one that begins in 1974, with his birth in the small city of Opole in what was then-communist southern Poland. His father worked as a high voltage maintenance engineer; his mother as an accountant at the police station. His only sibling, a brother, is nine years older. The family lived in a small one-bedroom apartment, where his parents slept on a pull-out couch.

Eric has pleasant memories of that childhood, which included annual family holidays at state-run resorts around Poland. When Eric was seven, his parents said it was once again vacation time. Bags packed and car loaded, off they went. This time, however, they crossed the border into Czechoslovakia and kept driving into Austria. On day two, his parents had some news: This wasn’t a vacation.

“I remember them turning to my brother and me. They said: ‘We’ve left home and we’re never going back,'” he recalls. “I was seven years old. I burst into tears and I’m like: ‘Oh my God: My friends and my LEGO and my Dinky toys – I’ve left them all behind!’ So my dad promptly took me to a gas station, bought me some toy cars to play with, and I was fine.” (His teenaged brother, who had been desperate to escape, was thrilled.)

They checked in at a refugee camp in Austria, then were transported to lodging in the Austrian alps housing other political refugees from Poland. That would be home for five months. Eric started Grade One in Austria, learning German. His parents wrote letters to Canadian, Australian and American embassies to see if they might be accepted as immigrants.

Eventually, Canada opened the door. And the Saczuk family arrived in Winnipeg on November 12, 1981. It was in the midst of a raging blizzard. There were no skyscrapers, no flashy buildings – none of the things he’d expected from seeing US TV shows like Dallas and Kojak.

“I thought we were in freaking Antarctica,” laughs Eric.

Below: Eric, second from right, and his family

CHAPTER TWO

The Sackzuks began their new lives. And one outing, when Eric was eight, proved a seminal event. His father took him to an air show that happened to feature the legendary McDonnell Douglas F15 Streak Eagle, a stripped-down fighter jet so powerful it could accelerate while in a vertical climb. The aircraft ultimately set eight records, including reaching an altitude of 98,425 feet just 3 minutes and 27.8 seconds after brake release (it then coasted to 103,000 feet). Eric was absolutely awestruck.

“So I saw this thing, full after-burner, go ballistic up into the sky. I’m like, ‘Holy shit, that’s what I wanna do.’ So, from then until I was probably 18 I just ate and slept and pooped airplanes. That was my life.”

He frequently cycled the 15 kilometres to the airport to watch aircraft. He read every aviation magazine or book he could get his hands on, including Ground School manuals. He was obsessed. When he was 15 and a half – the earliest age possible – he applied for the Canadian Air Force Reserves. His security clearance took nine months due to his background in a then-communist country. As he was wrapping up Grade 10, he was accepted to become an Airframe Technician at Squadron 402. His first day of training, he was surprised to see an old pal he hadn’t seen in years in the same CAF classroom – another immigrant from Poland. He and Martin remain friends to this day.

Because it was the reserves, it was a part-time gig. He went through basic training, including Ground School, and by the time he was in Grade 12 the CAF said the next step was for them to head to CFB Borden in just two weeks. That would mean leaving Highschool. But not having Grade 12 would eliminate the potential to become a pilot or reach officer ranks. Couldn’t they just graduate first and then continue? The answer from the military was no; it was now or never. Eric and Martin decided to leave and were granted Honorary Discharges.

But then what?

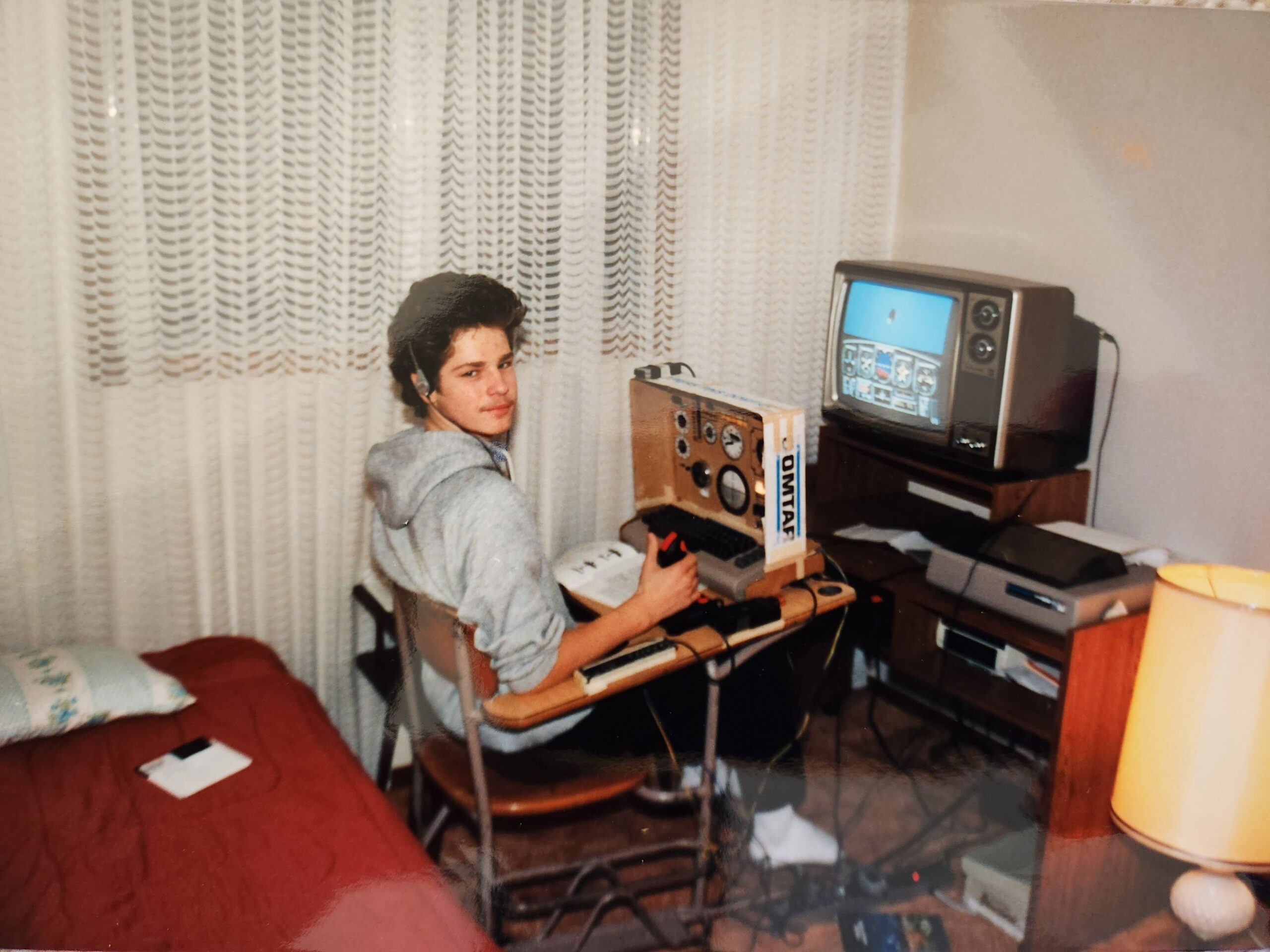

Below: Eric working a flight simulator in his teens, and in his CAF Reserves uniform

CHAPTER 3

We’ll fast-forward here. Eric applied to the University of Manitoba and was accepted into a geophysics program. It was math-heavy and he struggled. His GPA was under 2.0 and for a time he was on academic probation. That is, until he took a summer physical geography course that focussed on map interpretation.

“They put some aerial photos in front of me and I thought – I know this stuff. Because I’d been doing mission planning or flight planning for years and looking at aeronautical charts. And I’m like: ‘This is so simple.'”

He switched from geophysics into physical geography. He started specialising in a realm of cartography and satellite remote sensing, with an emphasis on geomorphology, “looking at natural hazards like landslides and debris flows and rock fall and flooding. How do we map these things? How do we analyse them in a geospatial way?” By his third year, that GPA jumped to 3.4.

Two academic advisors, both adventurous in their own way, would have great influence on Eric. One of them attached multispectral cameras to a powered paraglider to obtain aerial data, long before the days of drones. The other, an accomplished alpinist who had first ascents of multiple peaks in the Himalayas, took Eric to the Rockies in Alberta for research. The sheer beauty, in conjunction with the geomorphology, touched Eric’s soul in a parallel not dissimilar to seeing that Streak Eagle in his childhood.

“I fell in love with that. I knew this was where I wanted to be.”

For the next several years while obtaining his Masters and then PhD, Eric spent his summers researching amidst geological beauty: Banff, Yoho, Jasper, and Kootenay National Parks. Sometimes he would be living and working from a tent. During one miserable evening, cooking canned food from a camp stove, he spotted someone looking incredibly cozy in a camper van. He soon began a search for his VW Westfalia.

That love of natural beauty (Eric says he’d become something of a “tree-hugger” by this point), eventually led him and his girlfriend to Vancouver (along with a 1989 Westfalia he purchased after flagging down someone driving one at a stop light in Winnipeg). They married and soon there was a daughter on the scene.

He got a gig as a sessional lecturer at Simon Fraser University, and eventually became a professor at BCIT. When drones came on the scene, he saw their geospatial potential and immediately embraced them. He travelled to Antarctica working with drones, did PhD research in India, filmed a documentary in Nepal, hacked his way through forests in the remotest parts of Borneo, and also emerged as a professional photographer. The breadth of these travels, and others, led to him being admitted to The Explorers Club at its highest level. He also became head of BCIT’s RPAS Hub, immersing himself in geospatial and multispectral imaging and data analysis and teaching others.

His first marriage ended, but in 2016, he and Irina married under an arbutus tree on Salt Spring Island. She too had a daughter the same age as his own and they became a blended, happy family – which has collectively enjoyed many adventures in that Westfalia (purchased with 28k on the odometer and now approaching 500,000).

Below: Eric and his family camping with that Westfalia, followed by a mysterious tree in Borneo (which will be explained) and a highly meaningful tattoo

EPILOGUE: THREE TREES

The story of Eric (whose Polish name is ‘Arek’), is filled with many other adventures we wish we could include. But there are three brief things worth mentioning as we wrap things up. Remember that trip to Borneo? He went there to assist with an international forest research group, using satellite data to determine the age of rattan plantations. This wasn’t a basic trip, it was an expedition – involving days of hacking through dense forests with a guide. On the third or fourth day, in the middle of nowhere, they reached a section that looked starkly different. The trees were spread out, with a high canopy. The undergrowth they’d pushed through for days was gone. A local guide told Eric this was primordial forest; the trees here had never been cut down.

Some markings on one tree caught his eye. He looked more closely and saw it was a word. The hairs on his neck prickled up. The letters were A-R-E-K were carved in the bark. His own name. How could this be? Turns out, Arek was also the name of a local tribe – and that carving was to mark their territory. But seriously, what were the odds?

“It was a wild, surreal experience to have so far from home.”

Eric has a large tree tattooed on his left arm. It has sparse branches with no leaves. One might assume it simply symbolises a connection with the natural world. And, in one sense, it does. Trees literally give us life, and – whether through CO2 or our own mortal remains – human beings do the same for trees. But it’s more than that.

“It’s my Tree of Death,” he says. Tree of what?

He explains: “As my family starts to age and aunts and uncles start passing away, I wanted a place for them to come and have a final resting place. So this tree is a home for them.”

Meaning, as time passes, he will add to that tattoo.

“When one of my family members passes away, they will become a little crow that lands on a branch.”

And there’s a final connection with trees. Eric wanted to explore opportunities with companies in the drone space on the cutting-edge. He had already been doing advanced thermal and multispectral work, so he was looking for a company pushing boundaries. He hadn’t found a fit, until he happened upon the InDro Robotics booth at a conference. The talk soon turned to BVLOS flights, Transport Canada trials using Command and Control over cellular, other missions that pushed the envelope. He asked where the company was based, where its flight testing takes place. The person told him they had a field at the north end of the island, a spot called Channel Ridge.

“Do you mean the one with the big arbutus tree?” asked Eric. Yeah, that’s the place.

“I got married under that tree in 2016,” he replied.

Eric soon met InDro Founder and CEO Philip Reece and was brought on for increasingly complex operations. He was hired in 2022 as InDro’s Head of Flight Ops. Whenever there’s a highly complex mission – ranging from work in Saudi Arabia and Brazil to urban wind tunnel research flights in Montreal, Eric gets the call and packs his bags. If it’s close to home, he takes his beloved Westfalia. He divides his time between InDro, his work at BCIT, and his family.

And so, not surprisingly, the adventure continues.