By Scott Simmie

There’s no question that drones have become an essential tool for First Responders.

They’re used to assess fires, document accidents, search for missing people and even get a sense of damage following a natural disaster like a tornado.

They’re also used by police on occasion to actively search for a suspect trying to evade capture. In such scenarios, you can imagine that officers might be highly focussed on apprehending the suspect.

That may have been a factor in an incident that occurred August 10, 2021. It involved a York Regional Police officer with an Advanced RPAS certificate, a DJI M210…and a Cessna. The incident is outlined in detail in a new Transportation Safety Board report.

(If you’ve read the report and just want to hear our take, skip to the end.)

What happened

On August 10, 2021, a student pilot and flight instructor were in a Cessna 172N on a typical training flight. They were on final approach to Runway 15 at Toronto/Buttonville municipal airport. And then, in the words of the TSB report, this happened:

At approximately 1301 Eastern Daylight Time, the student pilot and flight instructor heard and felt a solid impact at the front of the aircraft. Suspecting a bird strike, they continued the approach and made an uneventful landing, exiting the runway and proceeding to park on the ramp. After parking the aircraft, they observed damage on the front left cowl under the propeller; however, there were no signs that a bird had struck the aircraft.

So what did?

Shortly afterward, a member of the York Regional Police reported to airport staff that he believed a collision had occurred between the remotely piloted aircraft he had been operating and another aircraft. The remotely piloted aircraft, a DJI Matrice M210 (registration C-2105569275), had been in a stationary hover at 400 feet above ground level when the 2 aircraft collided. The DJI Matrice M210 was destroyed.

There were no injuries to either pilot on the Cessna 172N or to persons on the ground.

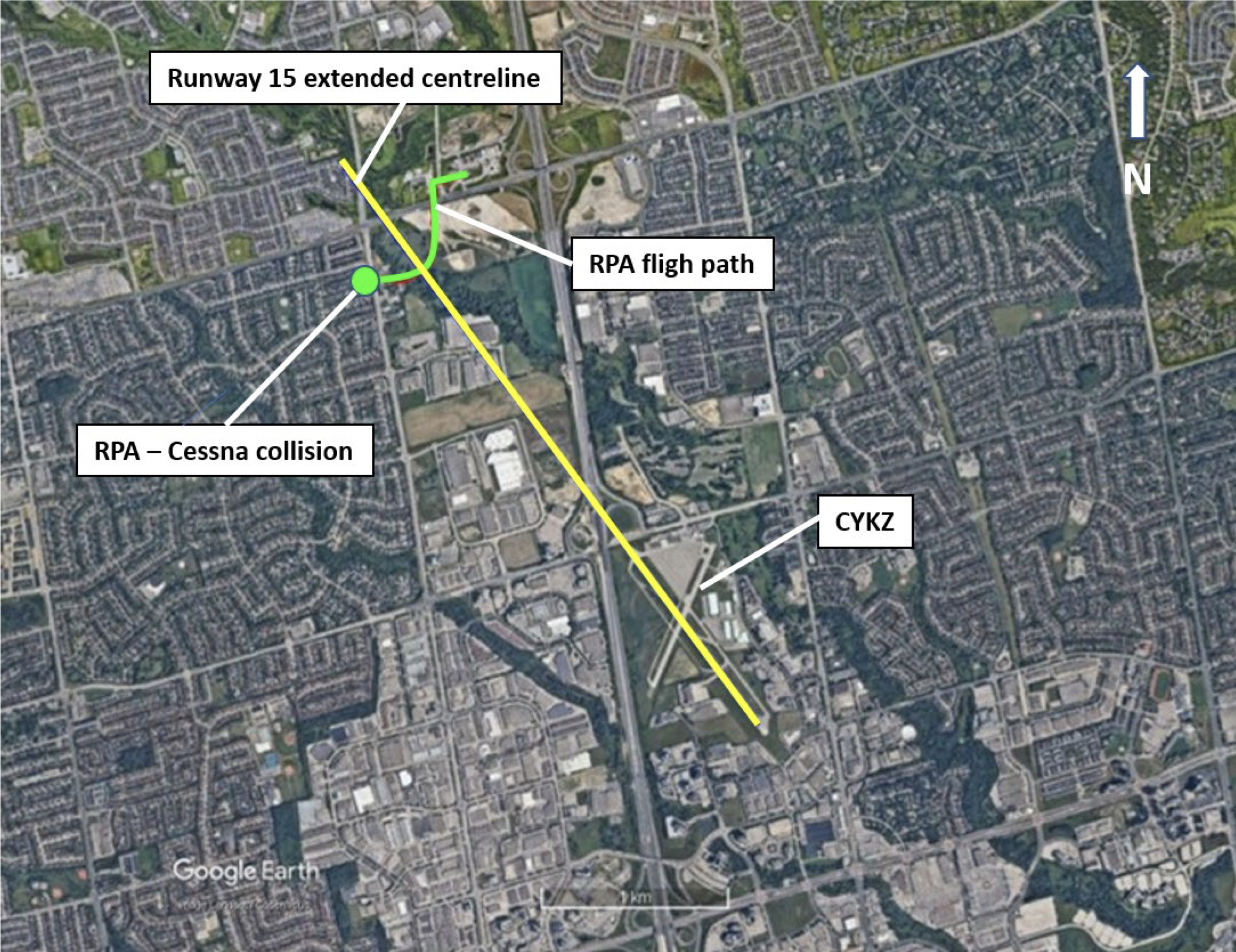

Here’s a look at the runway, along with the location of the RPAS. (Looks like the report missed a “t” on the word “flight.”)

The drone

York Regional Police (YRP) were looking for a potentially armed suspect, and called the YRP’s Air Support Unit (ASU) to assist at 12:02 pm. The pilot of the drone arrived at the scene at 12:20. The first flight of the DJI Matrice M210 took off at 12:32. Shortly after takeoff, the pilot asked some officers standing nearby to watch the drone during flight; one of the officers said they’d do the task.

After some initial reconaissance, the officer landed the flight 16 minutes later to change batteries. It was now 12:48.

“During this time,” says the report, “the pilots in the Cessna had completed their exercises in the practice area and were returning to the airport. They made the appropriate radio calls declaring their intention to fly over the airport and join the right-hand downwind for Runway 15. There was no other traffic broadcasting on the CYKZ mandatory frequency (MF) at the time, nor had the pilots heard any other transmissions on the frequency during their return flight.”

It’s worth noting the “Mandatory Frequency” here. This airport does not have a tower and its own Air Traffic Control. Aircraft are to announce their intentions over a mandatory frequency (124.8 MHz) and monitor that same frequency for situational awareness of other air traffic.

At 12:56, the DJI M210 took off for its second flight. The pilot, who was watching a flat-screen tv displaying the drone feed, took the drone up to 400′ AGL.

The pilots in the Cessna, meanwhile, were scanning for other aircraft as they began their approach toward the runway. They made a radio call with their intentions to land at 12:57. When the drone reached 400′, it was put into a stationary hover.

But that hover, unfortunately, was directly in the flight path of the Cessna. The report notes that a stationary black object, when viewed against urban clutter, would likely not have stood out to the pilots. When the aircraft was approximately 1.2 nautical miles from the airport, traveling at about 65 knots (120 km/hour), it impacted the drone at 13:01.

The Cessna landed without incident. But upon exiting the aircraft, this damage to the cowling was observed. There was also a slight scratch on the propeller.

And the drone?

Well, it was pretty much destroyed – as shown in this Transportation Safety Board photograph of the pieces that were recovered:

Other factors

The DJI drone was equipped with an Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) receiver. These pick up signals from ADS-B equipped aircraft in the vicinity, and issue a warning to the drone pilot. The Cessna was not equipped with an ADS-B unit, however, so no warning would have been generated.

The Report says the drone pilot was monitoring the airport’s Mandatory Frequency during operations, using a handheld VHF radio. The drone pilot also had his Restricted Operator Certificate with Aeronautical Qualification (ROC-A), allowing him to operate an aviation radio. Unlike the pilots in the Cessna, drone operators are not required to broadcast their intentions when in controlled airspace. In fact, NAV CANADA does not encourage RPA pilots to broadcast on those radios, as it can contribute to clutter on the airwaves.

But the report does point out an additional key responsibility for Remotely Piloted Aircraft operators:

RPA operators are required to receive authorization from the provider of air traffic services (ATS) to operate in controlled airspace (see section 1.17.2.1). The request for this authorization must include contact information for the pilot, and “the means by which two-way communications with the appropriate air traffic control unit will be maintained.”

When authorization is granted from ATS, a telephone number for the relevant ATC unit is included in the authorization. This telephone number is to be used in case of an emergency or loss of control of the RPA. This exchange of contact information between RPA pilot and ATS is meant to satisfy the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARS) requirement that two-way communication be maintained.

Flying a drone in controlled airspace requires obtaining clearance through NAV CANADA’s NAV Drone app. If the operation looks very complex and might involve greater than normal risk, the app will bump that request for a more careful review by Air Traffic Services.

But that’s not what happened. According to the Report, the NAV Drone app was not used at all in this incident.

The pilot of the occurrence RPA was aware of the NAV Drone application and knew that the operation on the day of the occurrence would take place entirely within the CYKZ control zone, therefore requiring authorization from ATS.

Due to the nature of the police operation underway, which involved a potentially armed individual, the RPA pilot felt a sense of urgency to get the RPA airborne as soon as possible. As well, the RPA pilot had not observed any traffic in the area during the set up of the RPA and had heard no recent transmissions on the hand-held VHF radio. As a result, the RPA pilot did not request authorization.

Interestingly, investigators later tested the NAV Drone app, requesting to fly an RPA at 400′ AGL at the location where the collision had occurred. The request was denied, and the app suggested they re-submit the request with a maximum altitude of 100′ AGL – a position far less likely to have caused problems for crewed aircraft on approach.

Role of visual observer

The TSB Report spends some time on this topic. It also documents what happened on that day in October. It appears that the role of visual observer was not explained to the officer that took on the role. And it also appears that officer spent most of his time looking at the video feed from the drone, rather than maintaining Visual Line of Sight with the drone itself:

During the day of the occurrence, the RPA pilot asked for another officer to be a visual observer. Although a nearby officer acknowledged the request, the RPA pilot did not confirm who, among the officers present, would assume that role, nor did he inform that specific officer what their duties or responsibilities would be. The officer was not aware of the requirement to maintain visual contact with the RPA.

The officer who was acting as the visual observer was observing the TV display for much of the time that the RPA was airborne and did not see or hear any airborne traffic, nor could he recall hearing any radio calls over the RPA pilot’s portable VHF radio.

The report also notes that the drone pilot did not use the York Regional Police’s mandatory RPAS Pilot Checklist, and instead relied on memory to prepare for the flight. It further suggests the pilot may have been ‘task saturated,’ – “restricting his ability to visually monitor the RPA and hear radio calls on the control zone’s MF and the sound of incoming aircraft, both of which preceded the collision.”

Some findings…

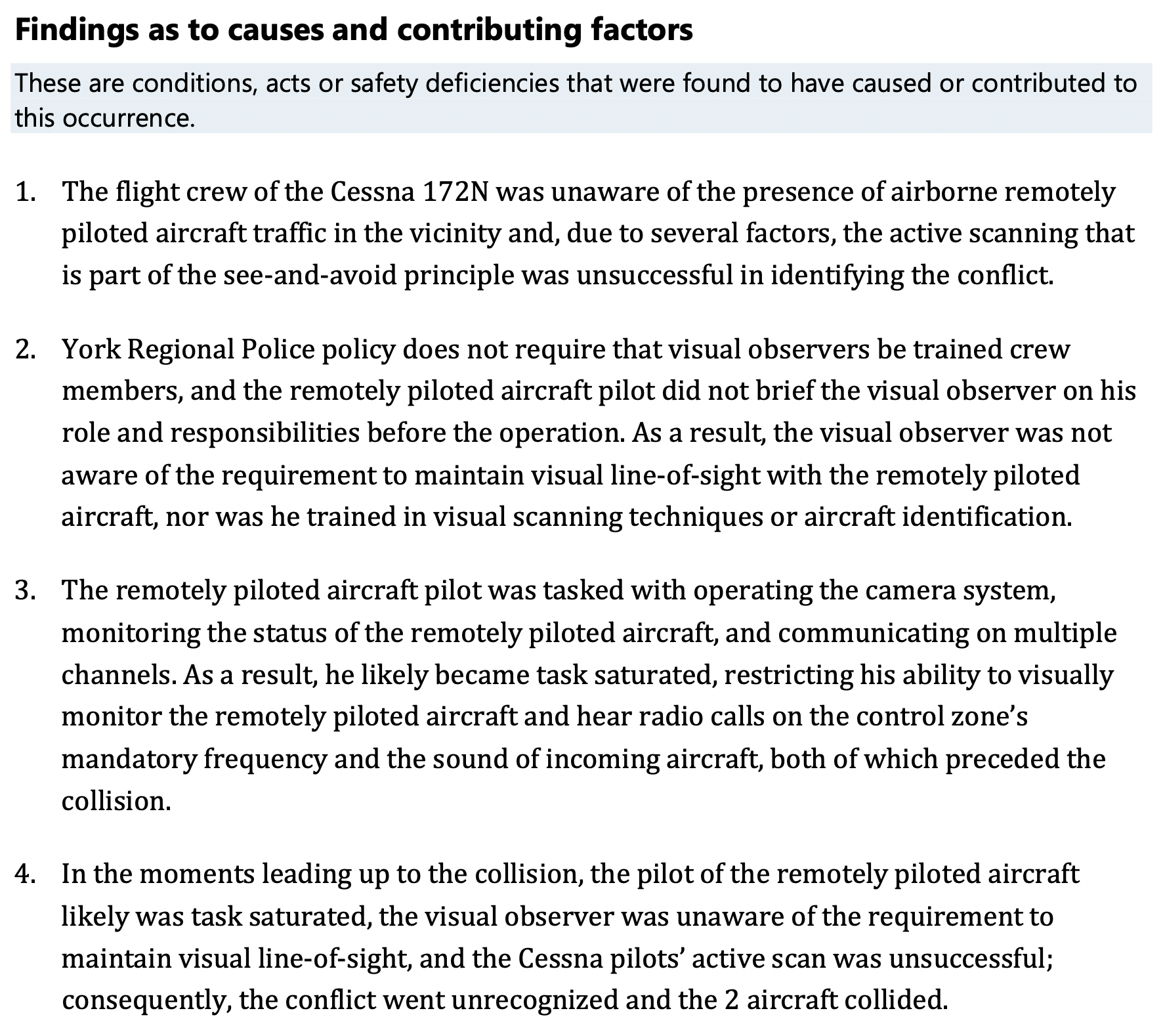

It is not the Transportation Safety Board’s role to find fault or blame. But it does identify contributing factors and/or causes that likely all played a role in the collision. Here are the four key findings on that count:

“Findings as to risk”

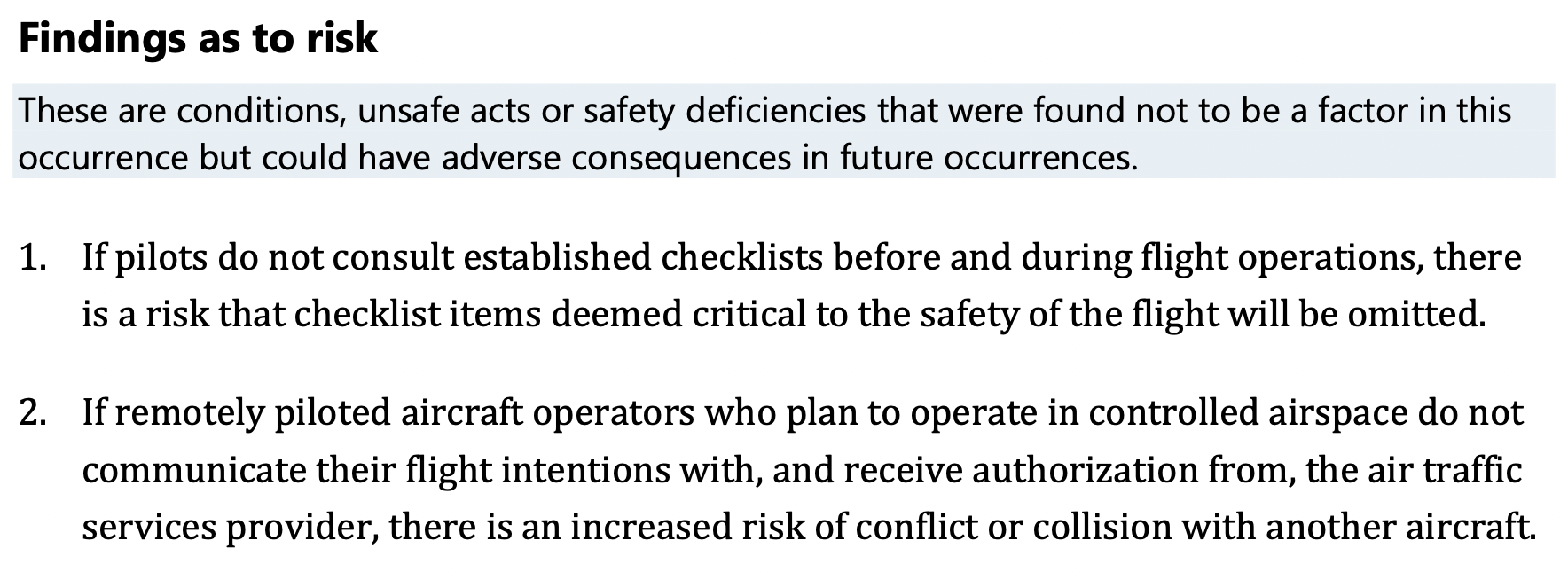

The report also notes two findings under the above category. It emphasizes that what appears below does not appear to have contributed to the collision, but could lead to adverse outcomes in the future:

Kate Klassen weighs in…

InDro’s Kate Klassen is a drone and airplane pilot and has about 1000 hours instructing on the same type of plane involved in the collision. She’s also very familiar with the minutiae of RPAS regulations in Canada.

Klassen read this report with great interest and noted a few useful takeaways. In particular, how it appears the apparent focus on the task – catching a criminal suspect – may have obscured what should have been standard procedures.

“Typically First Responders have established with the Air Traffic Service providers that they can do the job and inform as soon as possible, rather than following the NAV Drone pre-authorization process the rest of us follow.” she says.

“So I think it’s less that they launched as they did, and more that they didn’t have the situational awareness to operate there safely. They were perhaps too invested in getting the job done, where they figured ‘It’s not going to happen to me’, and weren’t taking advantage of all the tools at their disposal. They probably didn’t realize how risky this location was, especially to be operating at that altitude.”

Briefing visual observer

Klassen also notes that the selection of a visual observer was not accompanied by any sort of thorough briefing – which would have included maintaining Visual Line of Sight with the RPA, monitoring the radio, and listening (along with watching) for any crewed aircraft.

“I think the situational awareness piece is important,” she says. “Have the radio on the right frequency, have the visual observer actively monitoring it. It can’t be just ticking the box that you’ve assigned someone the task.”

“A more effective trained role would be explaining or ensuring they have skill to listen in on the radio and build that situational awareness of where the aircraft are. Also monitoring the sky, listening for aircraft noise. If you can hear a crewed aircraft but not see it, that’s when it’s sketchy.”

Klassen has worked with many First Responders across Canada, and understands the pressure they can be under to get a drone in the air. The challenge is to follow Standard Operating Procedures despite that pressure – particularly in controlled airspace this close to an airport.

InDro’s take

Though no one was injured during this collision, it was a serious incident. The drone could just as easily have hit the windshield, the leading edge of the wings near the fuel tanks or damaged the landing gear. Thankfully, that didn’t happen.

The Transportation Safety Board report is both methodical and meticulous. While not pointing the finger of blame, it does highlight some procedures that most certainly could have been handled better – and likely would have, were the flight not so high-priority.

Accidents and investigations should be, in our view, viewed as learning opportunities. And in this case – whether you’re a First Responder or not – there are clearly lessons to be learned.