Freefly gets on Blue sUAS, shows off hybrid drone @AUVSI XPONENTIAL

The company’s Alta X drone platform has been elevated to a very desirable status.

“Our Alta X was approved for the Defense Innovation Unit’s Blue sUAS list, which is huge for us,” says Freefly Chief Technical Officer Max Tubman. The ‘list’ is a small collection of drones that have been vetted for cybersecurity and components to ensure it meets the standards of the federal National Defense Authorization Act. It’s also seen as kind of an approved list of drones for purchase by the Department of Defense and many federal agencies using federal dollars for their spend.

“Going through the DIU process, basically has a third party validate all of your claims,” says Tubman. “They look at your supply chain, build material, operations, make sure your drones are secure from a cybersecurity standpoint. It allows federal agencies and private companies to know they’re buying an approved drone. And certain government agencies require that.”

Tubman says the company has already seen a significant boost in sales. What’s more, the company’s Astro drone is in the queue for the next round of potential approvals.

“It’s a big boon, yes. There are certain federal agencies that have just been waiting to replace fleets of aircraft so it will unlock at lot for them.”

That’s Tubman below, looking justifiably happy beside the Astro.

Hybrid en route

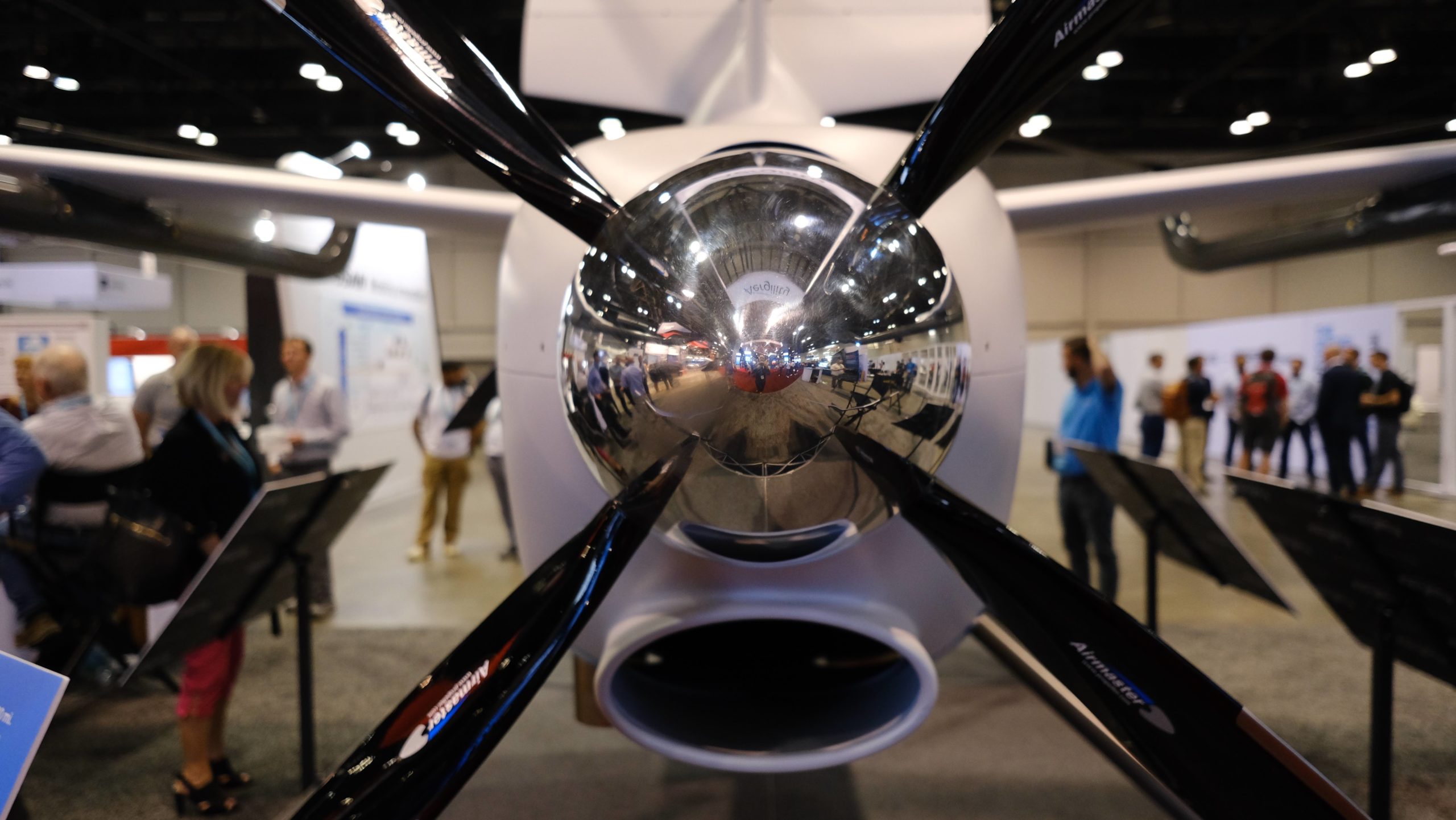

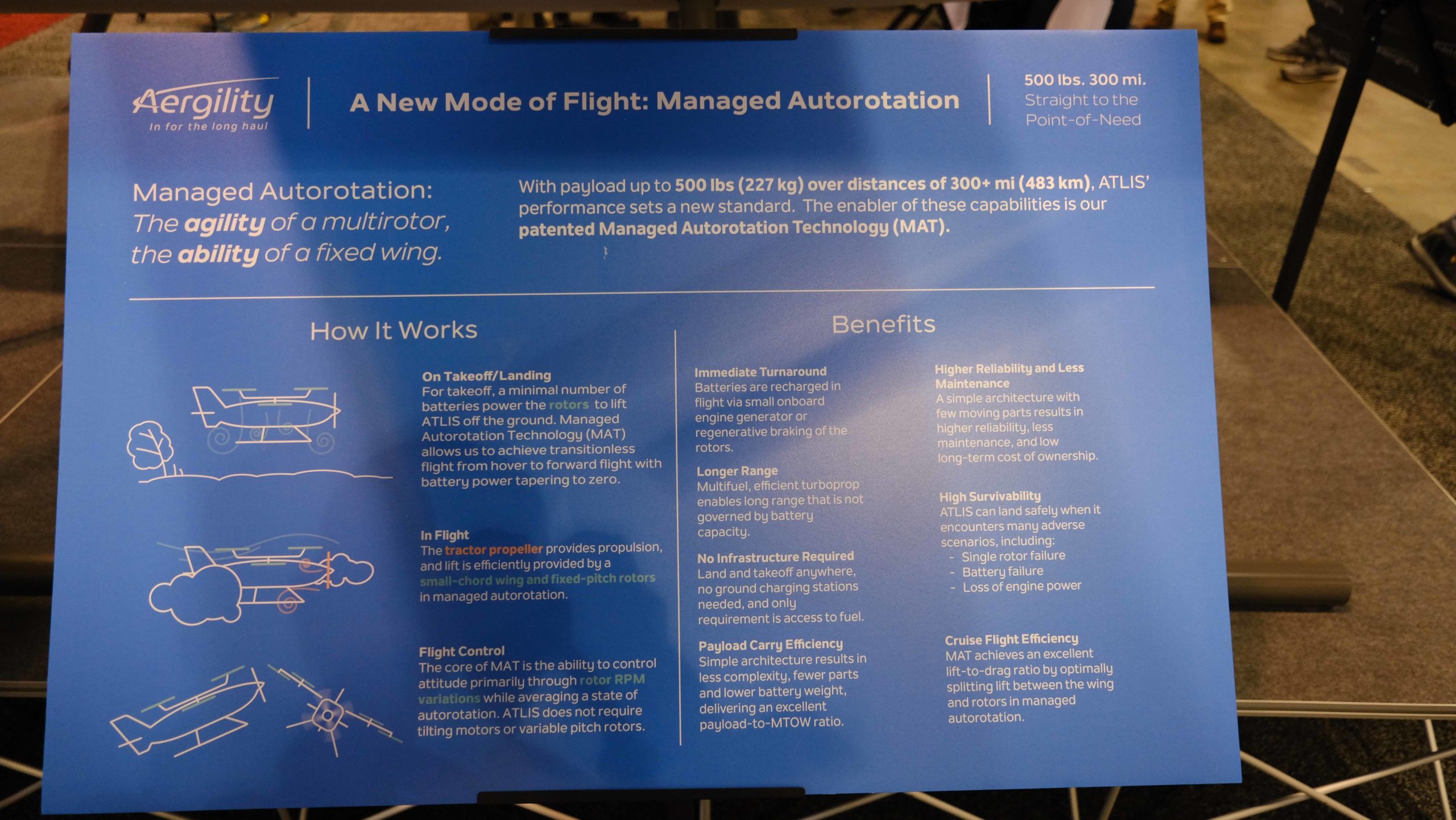

While the Blue sUAS news is big for Freefly, there’s some other big news in the wings. A new drone was on the floor, and it’s a marked departure from previous Freefly offerings. It’s a hybrid drone, using a gas-powered engine to generate power. And that’s a big deal.

“It has a four kilowatt, fuel-injected engine which allows you to fly for much longer time. We’re looking at LiDar payloads in the 10-12 pound range and flight times of 2-1/2 hours while remaining under 55 pounds.”

That’s something. Here’s a look at the Hybrid Hawk, which will likely be on the market by the end of the year.

The hybrid advantage

If you follow drones, you’ll know that the flight time for that kind of payload is pretty awesome. But what’s the secret sauce? The answer is that while lithium polymer batteries are great – they’re no match for the energy-to-weight ratio of gasoline (and this is actually a multi-fuel machine). It’s even better and more easy to deploy, says Tubman, than hydrogen fuel cell machines.

“It’s much easier and accessible than a hydrogen fuel cell,” says Tubman. “Hydrogen has a high energy density but a low power density, whereas gasoline has both a high energy density and high power density compared to a fuel cell.”

A Canadian Connection

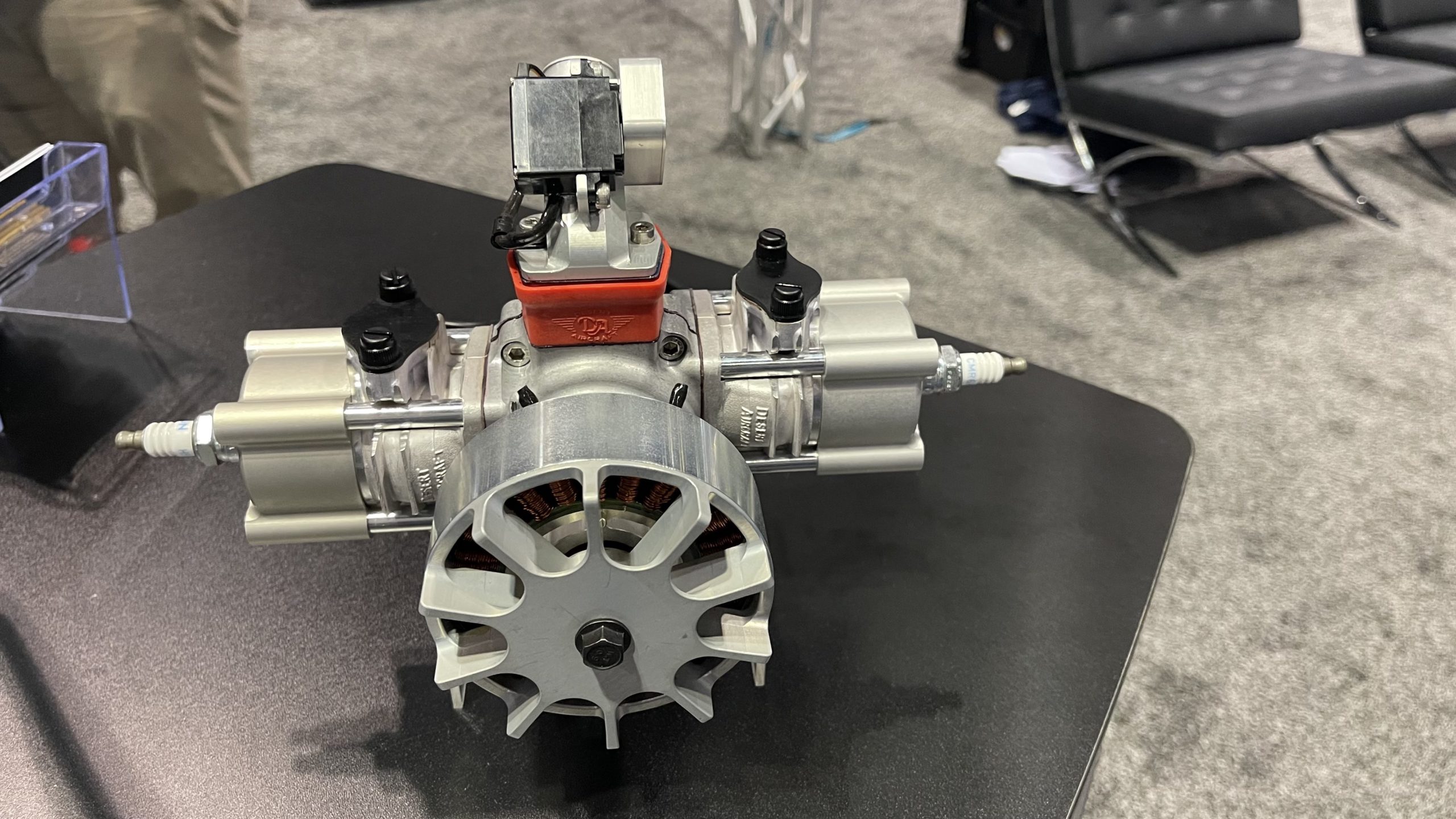

While Freefly is a US company, there was a collaboration with a Canadian company to get this machine made. The motor/generator combo was designed and fabricated by Pegasus Aeronautics, a company based in Waterloo, Ontario. Two of the Pegasus guys are in the photo above, with one holding the engine. Here’s a closer look at that powerplant.

Use-cases

Obviously, this kind of range has its advantages for inspection, surveillance and more. But it’s also hugely advantageous in remote regions where operators might not have access to power. What’s more convenient? Packing in thousands of dollars worth of charged batteries for a major job, or taking in a jerry can of gasoline?

“Having to haul batteries out into the field is basically a non-starter for a lot of these applications,” says Pegasus CEO and founder Matt McRoberts. “The ability to refuel a UAV and put it in the air and have it do useful work is important.”

And, for the geeks among us, here’s more about the advantage.

“The intention is that we take gasoline and use that as an energy storage method, which we can then transform to electricity,” he says. “As a consequence of gasoline having 40-50 times the gravimetric energy density as LiPo batteries, these types of systems can stay in the air much longer, up to eight to 12 times as long, depending on the application.”

Cool. So why aren’t we seeing tons of drones using gasoline to create electricity and extend flight times? Well, there are others – but not that many. And the answer, quite simply, is that extracting that efficiency to its fullest potential is no easy task.

What’s more, the Hybrid Hawk has software designed for BVLOS flight, including continuous monitoring of telemetry, motor health, power output and more. You can even start the engine remotely.

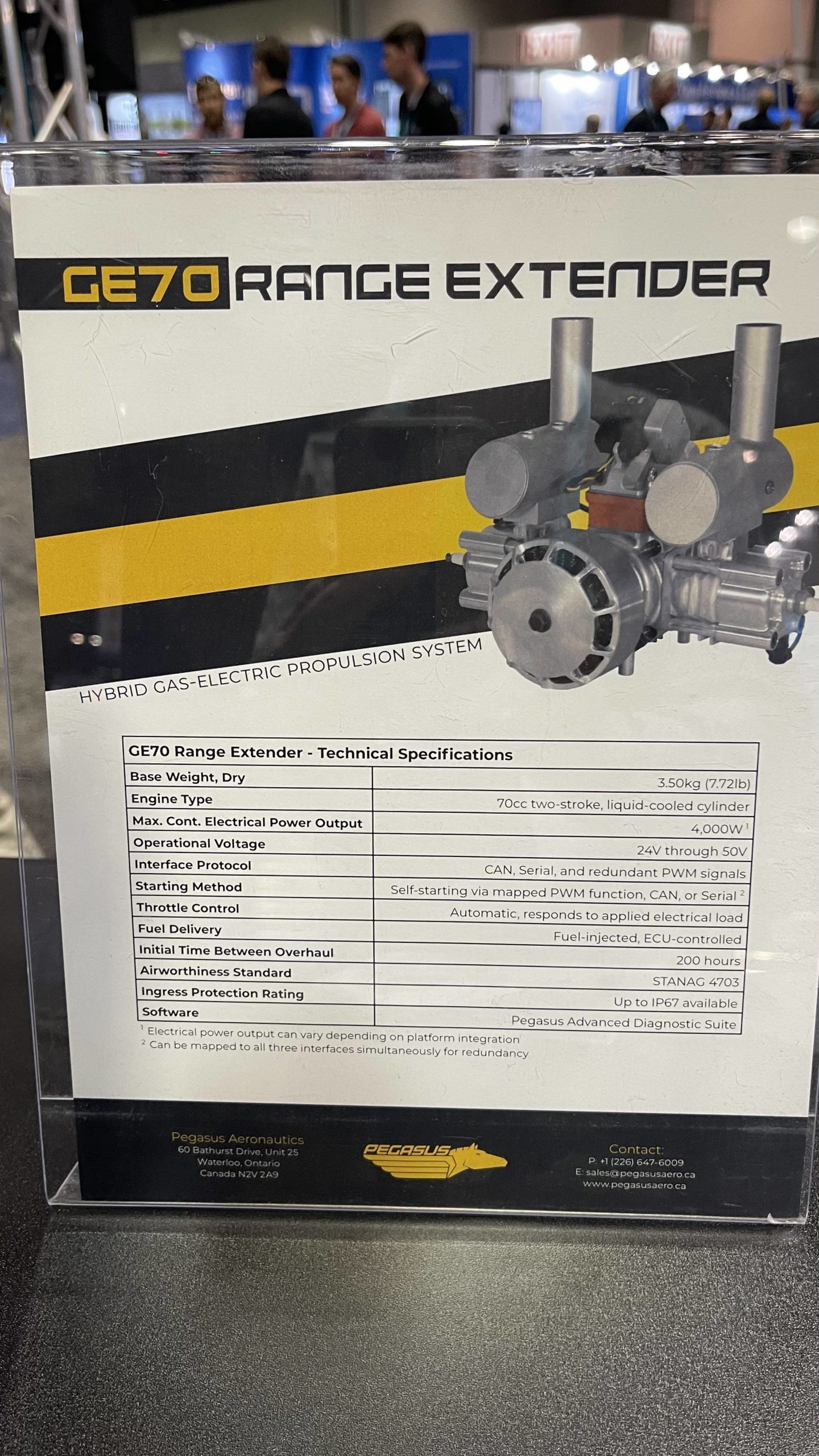

The motor’s spec sheet reveals that it’s a two-stroke, liquid-cooled cylinder. Other specs include:

- Four kilowatt power output

- Operational voltage from 24 thru 50V

- CAN, Serial, redundant PWM signals interface protocols

- Automatic throttle control

- Operation times before overhaul: 200 hours

- Ingress Protection: Up to IP67

There’s more there, too, if you read the fine print. Kudos to the engineers at Pegasus for pulling this together. It’s certainly no small task to build something like this.

InDro’s Take

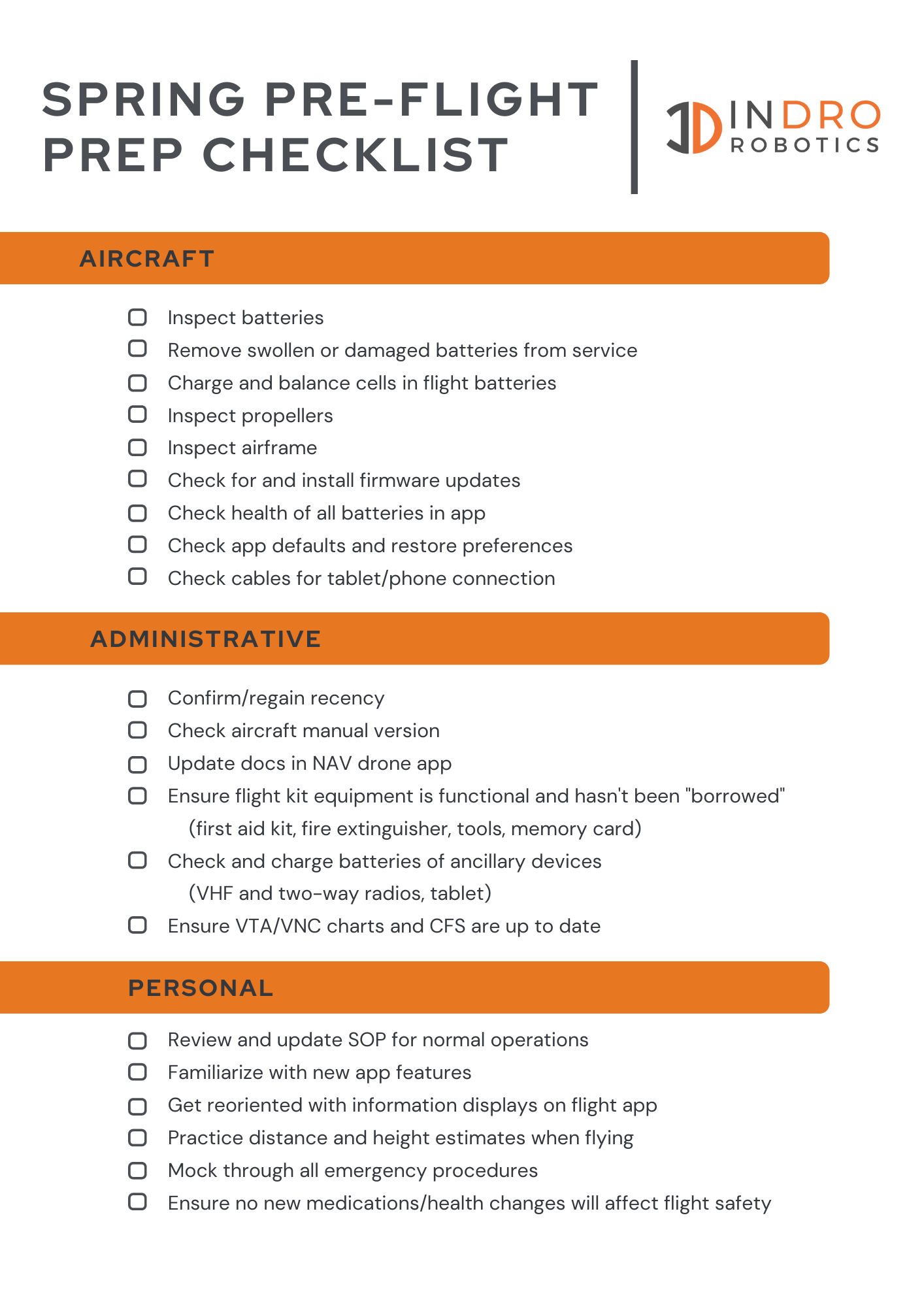

We can certainly envision the use-case scenarios for a UAS like this. The range and payload capacities open up a very wide door, particularly in remote and harsh environments where charging is not available, or the job is a big one. There’s a lot more efficiency in sending a drone up once for a large photogrammetry/data acquisition project, rather than doing it in bits and pieces. We also see great potential for deliveries beyond the range of most LiPo powered drones. And even on a very long delivery, it’s a simple task for people at the other end to refuel with standard gasoline (mixed with oil, of course), rather than ensuring charged batteries are awaiting for the return trip.

We look forward to seeing this drone get out of the gate, into production, and into real-world applications.