By Scott Simmie

There’s a buzz around Kelowna these days.

Well, actually, there are two kinds of buzz. The first is the occasional faint sound of a small but smart drone, carrying out flights every two weeks over two separate orchards. These orchards grow peaches, pears, cherries and more.

And the other buzz? Well, that’s the discussion this special two-year project – a collaboration between InDro Robotics and the City of Kelowna (enabled with funding from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Agriculture Clean Technology Program) – is generating among farmers in the region.

“Technology is always getting bigger and better,” says Riley Johnson, a manager at Byrnes Farms – one of the two locations where the project is being carried out. Johnson is an experienced farmer, and the land has been in the hands of his wife’s family for five generations. He knows the land and crops well, but is curious to see what additional data can be gathered.

“Anything in agriculture, the more information you get, you’re not going to be worse off. Especially for new farmers coming into the industry, any new kind of information can help out ten-fold – particularly if you’re on new land. Any information outside of the Old Farmer’s Almanac is always appreciated.”

What InDro is doing, to the best of our knowledge, is a type of precision agriculture that hasn’t been carried out before. It combines data acquisition from both drones and ground robots to ensure the most robust and reliable data possible.

This data is then used to assess overall vegetation health. Are there indications of pests in certain areas? Are any plants indicating low levels of chlorophyl? Does it look like that patch needs some pesticide – or maybe additional watering?

These are important questions for farmers whose livelihoods depend on maximizing the yield and health of their crops.

And this project? It’s all about finding the answers – and implementing solutions. Those solutions will include precision spraying of nutrients or other compounds in the precise location where they are required. The end result should be maximum yields with minimal – or no – areas of unhealthy crops.

Below: Healthy pears growing at Byrnes Farm. Photo courtesy Riley Johnson

AN INTRODUCTION

Before we get into all the details, it’s worth introducing you to Dr. Eric Saczuk (assuming you haven’t already met). He’s our Chief of Flight Operations – and comes with some serious chops.

Eric holds a PhD in Remote Sensing. He’s been assessing vegetation health (among many other things) using satellite data since the early days – long before drones came on the scene. But when drones did come on the scene, he quickly recognized their potential for the acquisition and interpretation of multiple kinds of data. He has flown missions all over the world on behalf of InDro, all involving complex data and analysis.

But that’s not all. He’s been an instructor at the British Columbia Institute of Technology since 2003 and has been the director of the institute’s RPAS Hub since 2016. He’s divided his time between BCIT and InDro since 2018 and is our go-to for highly complex operations. He’s also carried out multiple missions to acquire data for projects undertaken by Canada’s National Research Council – including this fascinating research on urban wind tunnels. There’s likely not a more qualified person in the country when it comes to drones and data.

Below: Dr. Eric Saczuk on an InDro mission. Image by Scott Simmie

THE PROJECT

Okay. You’ve most likely heard of precision agriculture by now. When it comes to drones, most of us picture something like this: A drone with a multispectral camera flies over a field of wheat or some other crop. That multispectral camera captures spectrums of light both visible and invisible to the human eye. When that data is crunched, it provides a detailed picture of crop health (we’ll explore more of this shortly).

In collaboration with the City of Kelowna and local farmers, we’ve been flying a mission every two weeks over two separate fruit orchards. We use a drone with a special type of camera. It has five lenses. One of those lenses simply captures RGB (or simply, colour) images. But the other four have filters that are tuned to pick up light only within specific spectrums that can be collectively analyzed to indicate the health of vegetation.

“So in addition to the RGB camera, you’d have one camera capturing just red reflected light, one capturing just green reflected light using filters, and then the other two are what we call red edge and near-infrared,” says Dr. Saczuk.

Red edge is particularly useful in the early detection of disease or stress in plants – as it is highly reflected by healthy chlorophyl. But the real magic happens when you take the data captured in these different light wavelengths of light and run some calculations on them. That’s what gives you the bigger picture.

“Think of each of these images as a number. Capturing these multiple spectral bands allows you to combine them using complex equations in a type of calculator to give you various indicators of vegetation health,” he says.

That data can answer a lot of questions.

“Is it healthy? Is it not healthy? Is it being productive? Is there chlorophyll? If so, how active is it?” he says.

“These are the kinds of questions we can answer when we do what we call ‘multispectral band combinations.’ And it gives us a really clear picture that cannot be detected by the human eye.”

A CLOSER LOOK

We’re going to take a look at an image in a moment.

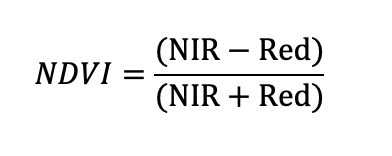

Before we get there, though, it’s worth exploring something Eric said earlier. He mentioned complex math. He’s right. The math happens at the individual pixel level between each of the input bands and there are millions of pixels per band. The most common calculation is used to produce a result called NDVI (not be be confused with NVIDIA, the producer of AI chipsets). The acronym stands for Normalized Difference Vegetation Index. And once the math is done, it gives you an accurate picture of vegetation health.

NDVI is calculated by using near infrared (NIR) and red bands (you’ll see the formula below).

The resulting pixel number in an NDVI image, will always be between -1 and +1. The higher the number, the better the health. If the number is low, it means there’s something worth looking at. The NDVI provides a detailed look at crop health and while it is regarded as the gold standard, there are also other calculations that can drill down to more specific indicators of vegetation health.

Below: Healthy vegetation absorbs most of the visible light that hits it, reflecting a large portion of the near-infrared spectrum. Unhealthy or sparse vegetation (right) reflects more visible light and less near-infrared light. When you do the math, it yields a lower NDVI number. (Public domain image by Robert Simmon.)

The second image is the equation used to calculate NDVI (which explains what those numbers are at the bottom of the first image).

FROM DATA TO DECISIONS

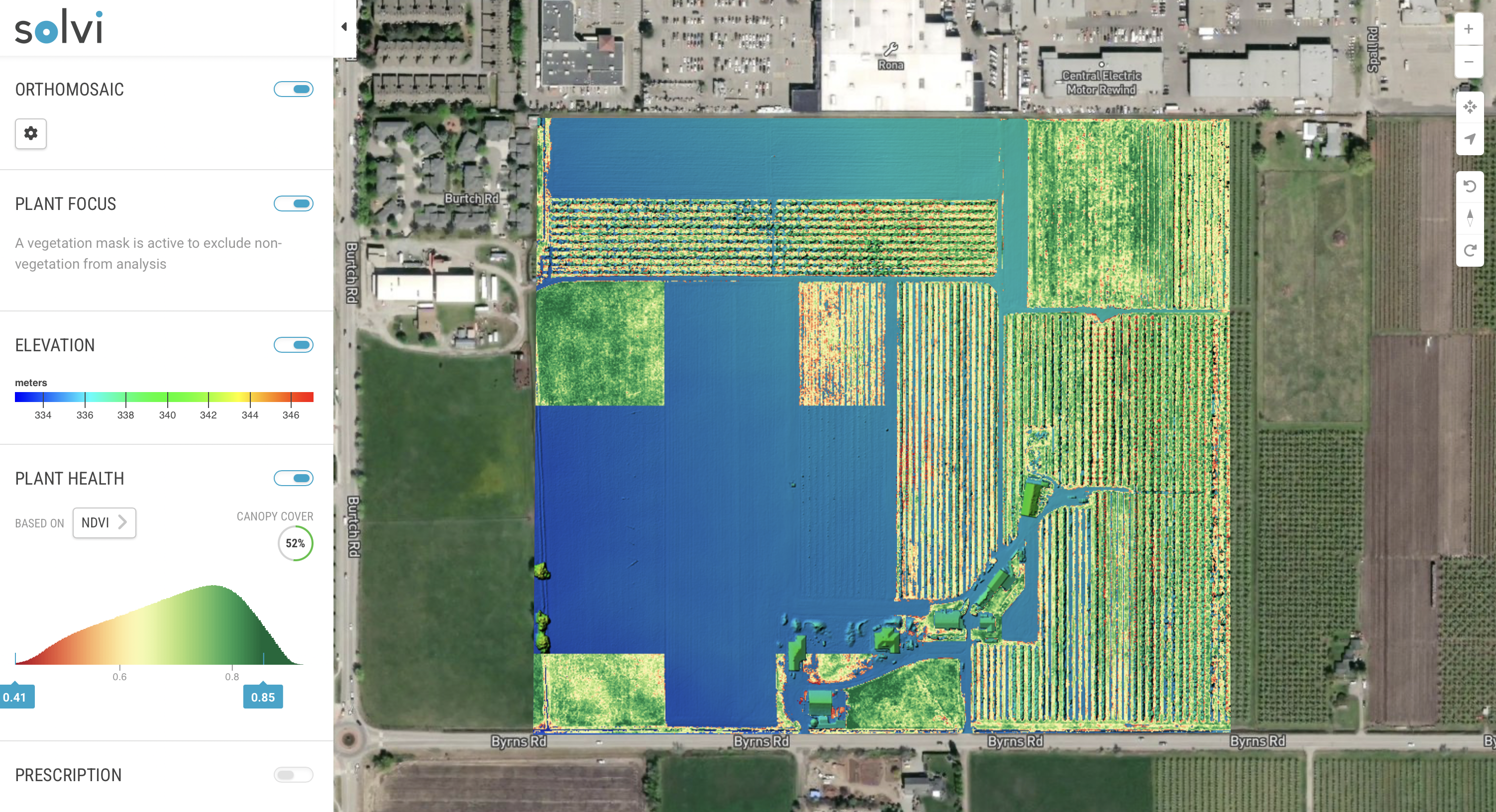

Using the equation above (as well as other formulas), Dr. Saczuk turns all of that data into something both meaningful and actionable. By looking at the data – and calculating not just NDVI but other indexes, images are generated that provide an at-a-glance look at crop health.

Traditionally, this has been a hugely time-consuming task involving multiple steps (and plenty of processing) on a laptop. Now, new tools are available that streamline the process. Dr. Saczuk is using a cloud-based solution specifically for precision agriculture.

“It really makes the whole process very efficient – because not only does it do the photogrammetry on the images, stitches them into these orthomosaics, but it also gives you the tools with which to analyse them. This would typically be a multi-step process, but this software makes it a one-stop shop, which is really nice.”

That’s without even getting into some of the AI capabilities of the software. It can, for example, count all the trees in a given orchard – and even give you the elevation of a specific tree.

Below: An NDVI image of one of the farms in the Kelowna project.

NOW WHAT?

At this phase of the project, InDro is gathering data by drone alone. But as it progresses, two more things will happen: We will introduce ground robots and precision spraying.

The plan is that a ground robot will initially be fitted with the same kind of multispectral sensor used by the drone. Autonomous missions will be plotted and the robot will capture a series of images from the ground as it drives through the orchard. That data will be crunched and compared with the results captured from the air.

“This is a way of doing ground-based validation of what we’re seeing from the air, from the aerial images of the drones,” says Dr. Saczuk.

Once that validation is complete and if problem areas are detected, the next phase would involve precision spraying – which could be carried out by an AGRAS agricultural drone – or even potentially by ground robot. Because all of the data is georeferenced, that means the fertilizer (or possibly pesticide or herbicide, depending on the issue) can be precisely applied to only the required locations. That, of course, is where the term Precision Agriculture comes from.

VICE-VERSA

This project is data-driven, with aerial and ground acquisition. But at the outset, shortly after our initial flight in April of 2024, farmer Riley Johnson noticed that a couple of trees weren’t doing well. It wasn’t clear what was causing this failure to thrive, but he didn’t want to take any chances that a potential disease might spread further in the orchard. So those trees were taken down.

In this case, because the issue was spotted early and the location was known, Dr. Saczuk is quite interested in doing some deep drilling into the data at that spot. In fact, that’s the very issue he has recently been exploring.

“So we’ve got that data, that information that’s saying, ‘Hey, these trees were actually not doing well.’ And then the next question is: Can we see anything in the multi-spectral images that would indicate that these trees are somehow spectrally or reflecting light differently than the ones that are healthy?”

This is something that is also of particular interest to Johnson. Will the data reflect what years of experience indicated was a problem to his naked eye?

“As the season progresses, it will be really interesting to see what InDro comes up with,” he says. “But I can definitely see the value of this for someone just getting into farming, or for farms up the hills with new plantings, new growth. This could be very useful.”

Below: Another image of a Kelowna orchard from this project, showing elevation

INDRO’S TAKE

We’ve been involved with precision agriculture projects in the past. In fact, we pioneered a “drone-in-a-box‘ solution, where we’ve shipped a drone to farmers. We talk them through the process of being a visual observer, then instruct them on how to power up the drone. InDro then carries out the flight remotely, using 4G or 5G – while in constant contact with the observer. When it’s done, the farmer puts the drone in the box and sends it back. InDro carries out the data analysis and quickly sends an easy-to-understand report indicating what areas require attention – and what kind of attention they require.

But this project is very different, and exciting for multiple reasons.

“The bi-weekly flights by drone will provide a huge amount of timely data, enabling us to detect any potential problems at an early stage,” says InDro Robotics Founder and CEO Philip Reece. “But by adding robots to validate from the ground, we’ll have a more robust dataset that can be used to truly pinpoint areas of concern and which may require precision spraying. We are going to learn a lot with this project – and believe our findings will be of great benefit to farmers down the road.”

A final note. When Dr. Saczuk isn’t carrying out these flights, they’re being flown by a new addition to the InDro team, Jon Chubb. He’s already had interest from other farmers in the Okanogan who are eager to maximize their own yields and have an early detection system for any trouble spots. If you’re in that neck of the woods and would like to arrange a demo, you can contact Jon here.