By Scott Simmie

The average annual temperature in India’s Gujarat state is 29° C – and that’s during the winter. In summer, it’s not uncommon to hit highs of 49°.

So you can imagine the shock when two teenagers from that state stepped off separate jets in Ottawa six years ago, just as a Canadian winter was setting in, to pursue careers in engineering.

Neither Ujas Patel nor Tirth Gajera, now valued members of InDro’s core team at Area X.O, had ever been abroad before, let alone out of their own state. And neither were highly proficient in English yet – though they had both studied in preparation to attend Algonquin College. Their native tongue was Gujarati.

For Ujas, his father – a mechanical engineer – had been the inspiration. Ujas was fascinated with what his father did, and spent several months working with him on projects to learn more about the field. His father, meanwhile, encouraged his son to study abroad, and specifically in Canada. The year was 2018 and Ujas started preparations – applications, studying English, student visas and other documentation – and figuring out which city to choose.

“I could have gone to Toronto or any other part of Canada, but I realized that in Ottawa there are not so many international students, and I wanted to live with Canadian people,” he recalls. “I wanted to learn what they do, how they live life.”

Tirth Gajera, meanwhile (who we’ll refer to as T going forward), was going through all the same preparations. T knew he was interested in aerospace or a related field, and had been encouraged by others to start with a mechanical engineering course abroad. Going to either the US or Canada were the best options. Things in the US were a little dicey at the time, so the choice became Canada – and specifically, the same institution that Ujas had chosen: Algonquin College in Ottawa. The two had never met.

And so, in November and December of 2018, each landed in the nation’s capital. And a challenging, at times gruelling, life-changing journey began for both of them.

Below: T and Ujas, on the days they left India for an uncertain future in Canada

A WORLD APART

If you’re not an immigrant, try to imagine the challenges of landing in a new country where you have virtually no connections – and not even a place to stay. You speak the basics of the language, but you’re by no means proficient. Absolutely everything is different: From the weather right down to the unfamiliar products in a grocery store. Picture also that you’re 17 or 18, and that this is your first-ever trip abroad – and that you are alone. To further complicate things, tuition, rent and the overall cost of living are high and you don’t want to burden your family back home (where the annual income is much lower than in Canada).

This is the reality Ujas and T faced on arrival in Ottawa.

T recalls meeting another young man from Gujarat at the Ottawa airport. The new friend was in transit, waiting for a friend to pick him up who would drive him to Montreal. T had no idea where he’d be spending the night. When the ride for his friend arrived, T told them “I don’t know where to go.”

Luckily, the driver knew of another friend who might be able to help. He called him, and a stranger came and picked T up at the airport.

“He showed me around, and said ‘You can just stay with us for a week until you figure out something.”

Ujas, meanwhile, was also alone and trying to figure things out. Someone from Algonquin College had arranged a place for him to stay for just a few short days, but he was also on his own.

“I was the first in my whole family to come here to Canada,” he says (his sister has since moved to Kitchener and recently graduated as a Registered Nurse).

Ujas also knew, like T, that the cost of living was going to be a quantum leap from living at home in Gujarat. He’d have to find an apartment, pay utilities and public transport, buy groceries. All in a strange new world. Plus, both young men knew they’d have to find work to pay for their studies. The cost was high, and it was a burden neither wanted to shift back to relatives at home.

“I could not ask my parents to pay for my tuition fees because as international students, we were paying like $8000-$9000 for each semester,” says Ujas. So they would have to find work.

SECOND THOUGHTS

Not surprisingly, there were frequent calls home in those early days. Both felt alone, and connection with their families was a crucial thread that helped keep them going at the beginning.

“I used to talk to my parents and close relatives every day or every other day,” says T.

In addition to the stress of feeling like strangers in a strange land, there was also the weather to cope with. T had bought what was billed as a winter jacket back in India. But the winters in India were so mild that the jacket afforded barely any protection. One night, early into his stay and feeling low, T donned his jacket and prepared for a walk. While the temperature wasn’t bad by Ottawa standards, maybe -1°C, in that jacket he was freezing. He felt bleak.

“I stepped out of my house,” he recalls. “And I walked for about 500 metres and I started crying. I was like: I want to go back to India. This is too cold. I might just die here. The experience was definitely kind of hard, I can’t even explain it in words.”

Understandably so. But T and Ujas would push on, finding work and preparing separately for their first semester studying at Algonquin College.

“And then,” says T, “it all started coming together. I started going out, started meeting people, things like that.”

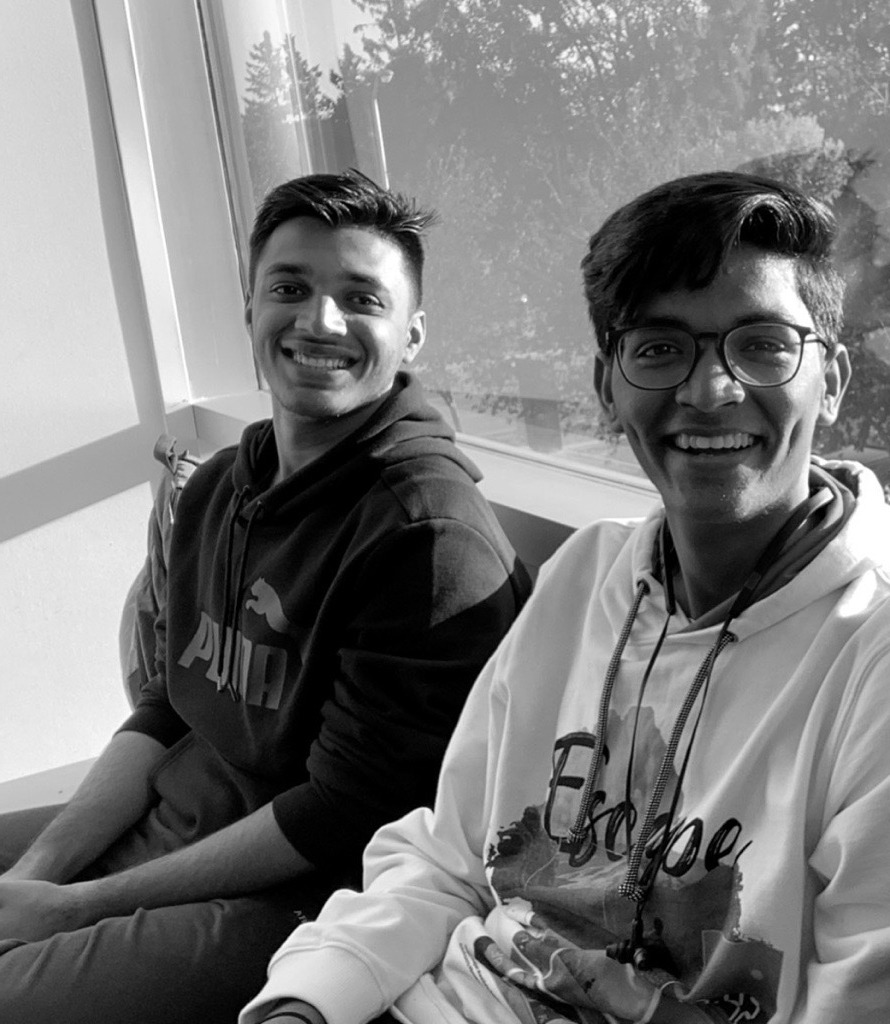

Below: T (l) and Ujas after meeting at Algonquin College.

SCHOOL-WORK BALANCE

Ujas and T would meet for the first time on the first day at Algonquin College during orientation. Both were enrolled in the three-year Mechanical Engineering Technology course. They hit it off immediately and would become not only fast friends, but part of each other’s mutual support system.

The courses were challenging and very much hands-on. There were about 26 hours of lectures and labs per week, plus assignments that had to be completed daily. As anyone who has taken engineering knows, the workload is punishing. But there was also that crushing cost of living, which could not be ignored. So both Ujas and T took part-time jobs on top of their classes. Both became, initially, “junior sandwich artists,” making subs at Subway and Firehouse Sub franchises.

“That was my first job,” says T. “And all of my colleagues were Canadians.”

During breaks between semesters, both would cram in as many hours as possible to earn money.

“I used to work 60-70 hours a week just to just to get my fees done so that I didn’t have to ask my parents to send me money here,” says Ujas.

ALGONQUIN COLLEGE

When classes were on, school had to be the priority. The pair hadn’t come halfway around the world just to work; that was simply a financial necessity.

“I had to manage my all assignments, had to make sure I was doing well in my studies. But at the same time I had to make the money to pay for my place, my rent, my food, everything.”

Both T and Ujas immersed themselves at Algonquin College, and were soon working on complex projects together. They built a basic semi-autonomous vehicle, which with limited sensors could explore an unfamiliar room. They created a pneumatic system that duplicated how the doors on Ottawa’s public transit buses worked. They learned hands-on work with electrical and mechanical components, coding, and more. Both excelled in their studies.

The program was supposed to include a co-op section, where students would build on their skills (and earn money) working with a real company. And then, of course, COVID hit.

“This was a tragedy,” says T. “We were doing interviews for the co-op placements and then the pandemic came along. The school said: ‘You’re not doing co-ops or anything. You’ll all just have to stay home.'”

T found a job with a call centre; a job he could carry out from home. He worked there for eight months, a position that really helped him improve his English. Ujas worked at a gas station. Then, finally, it was back to courses at Algonquin for the completion of their degrees.

Below: Ujas on graduation day, followed by a trip to Quebec City. His dog’s name is Loki. T enjoys playing guitar when he’s not at the office

TEAM INDRO

A few months after graduating, Ujas happened to see a job posted by Invest Ottawa. It was with InDro Robotics. He came in for an interview with Engineering Manager and Robotics Engineer Arron Griffiths (MSc).

Arron saw a potential fit, and offered Ujas the position. He would also become a mentor, helping to fill in knowledge gaps and supporting him with learning many new skills. This was his first-ever job in his chosen field, and soon – with support from Arron – he was working on complex robots. He also obtained his Advanced RPAS Certificate, and was selected to be the second pilot (working with Eric Saczuk) on a highly complex mission in Montreal for the National Research Council.

The mission was to measure urban wind tunnels – and involved flying a heavy industrial drone equipped with dual anemometers between buildings, Beyond Visual Line of Sight, and over people.

“Flying a drone is easy,” says Ujas. “But when it comes to flying a drone over people and between the buildings of Montreal, that’s really hard.”

Ujas has had a hand in pretty much all the high-level projects at InDro, including custom robots for clients and many of the InDro innovations. He’s also InDro’s go-to for building when orders come in (as they frequently do) for InDro Commander. He’s also worked on several InDro projects that involved manipulator arms.

Two and half years after joining InDro, it’s been a terrific fit.

“Arron tells me I’m like a completely different person when it comes to skills from the person who started here,” says Ujas. “He has played a major role for me. The experience I have, the amount of knowledge I now have, it’s all because of him. Plus, CEO Philip Reece and Vice President Peter King have always been supportive mentors.

“I can say I’m really proud of the work I’ve done here. “

AND T?

T found work with two large companies after graduating. But the work, which involved overseeing manufacturing lines and doing technical troubleshooting, wasn’t that satisfying. He was more interested in software – and greater challenges. Ujas, meanwhile, saw an opening at InDro and T was introduced to Arron. Once again, Griffiths spotted potential synergy. So did T.

“The job was an amalgamation of electrical, mechanical and software. And I thought, yes, this is going to be a good fit.”

And it was. Soon, again with Arron’s guidance, T was taking on more and more complex projects. He also started offering ideas of his own, such as how to make a slimmed-down version of the original InDro Commander, which was a bit large on some platforms. He also came up with the idea of writing some code for networking that would enable InDro robots to operate over WiFi in addition to teleoperations. Pushing dense data through a SIM card can quickly add up costwise, and many of InDro’s academic clients are on limited budgets.

“All the robots that we had, all of them could only be connected to cellular,” says T. “But using a SIM card for data is expensive.” T thought the problem might be solved with writing code and flashing off-the-shelf routers to enable them to transfer data via WiFi.

“This eliminated the need of always having to go into a robot for development through a cable,” says T.

He also started the initial work on InDro Controller – the secure dashboard for remote operations and autonomous missions. And one robot, which had two manipulator arms, was pretty much a solo project for T.

“I did all the software, all the networking, all the hardware,” he says. “That was my first robot that I built from scratch.”

As with Ujas, T has played a significant role in multiple projects over his two years with the company and has become an integral member of the team.

“Ujas and T have come a long way since they walked in the door at InDro,” says Arron Griffiths.

“From the start, they’ve always been team players, eager to learn more skills and think of new solutions. They both have strong and positive work ethics and have really developed broader skillsets in multiple disciplines since arriving.

“They are both valued members of our team and a delight to work with. My gut sense about both of them at the time of hiring proved to be right.”

As for the young men from Gujarat?

T says it’s been a phenomenal workplace, always filled with new challenges and the opportunity to take on projects that appeal to him.

“Arron has never been: ‘Oh, you’re just a mechanical engineer so focus only on hardware.’ He’s never stopped me from working on things that appeal to me – and that has really helped expand my skillset and satisfaction working with InDro.

And Ujas?

“It’s been a long journey,” he says. “But a great one.”

Below: Ujas (bottom left) and T during a lighter moment with Stephan Tozlov, now Production Manager at InDro Forge

INDRO’S TAKE

It has, indeed, been a long and fruitful journey for Ujas and T. We could not be happier that they chose Canada – and that InDro chose them.

“Both T and Ujas are truly valued members of Team InDro,” says Founder and CEO Philip Reece. “They’ve grown with the company and made valuable contributions to many projects. The same kind of work ethic that drove them both during those early and difficult days in Canada is seen every day on the job at Area X.O. We couldn’t be prouder of them, and the journey they’ve made.”

We look forward to continuing our occasional series of profiles of InDro Robotics staff. Up next? Engineering Manager Arron Griffiths.

Stay tuned.