By Scott Simmie, InDro Robotics

Scores of drone flights took place in restricted airspace – what you might think of as a ‘No-Fly Zone’ – over Parliament Hill in Ottawa during the police operation to clear anti-vaccine mandate protests in February of 2022. While some of those flights were carried out by law enforcement, most flights were illegal and in violation of Transport Canada regulations.

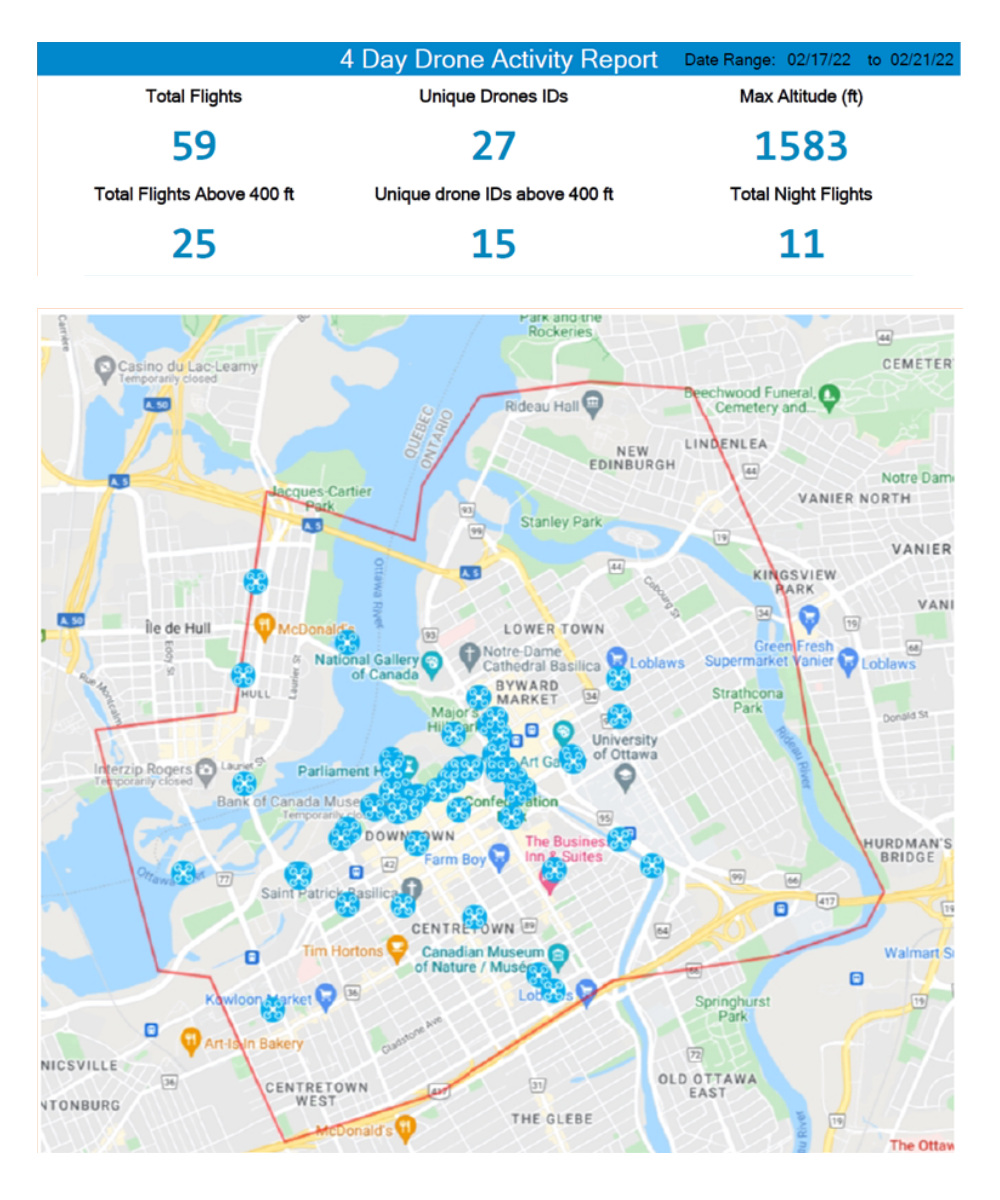

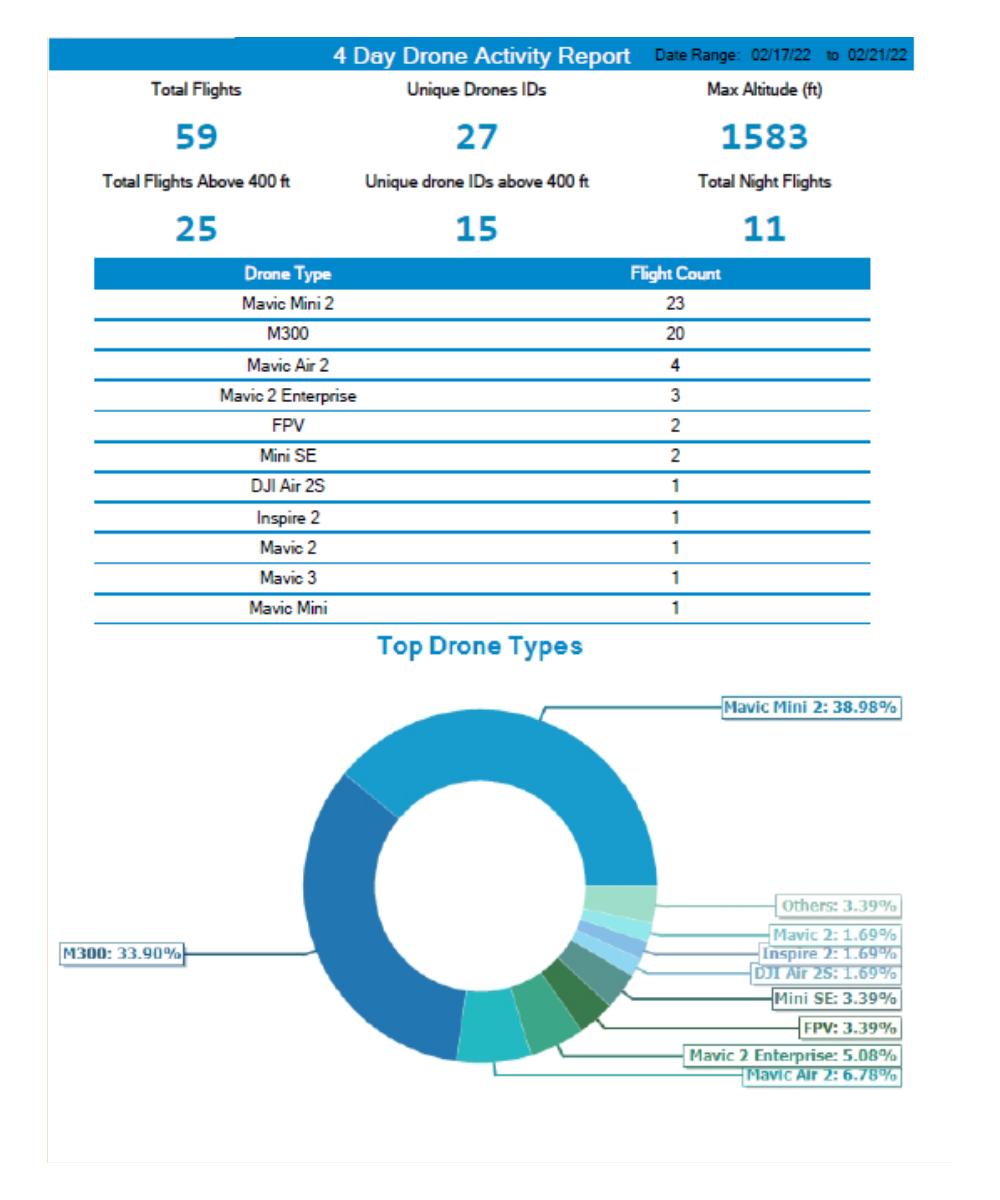

Data collected by the Ottawa International Airport Authority’s (YOW) Drone Detection Pilot Project reveals an incredible spike in flights – a total of 59 – during the days when police were actively clearing protestors from the site.

“In an average month, you’d probably see half a dozen flights (in that same area),” says Michael Beaudette, Ottawa International Airport’s Vice President for Security, Emergency Management and Customer Transportation.

A total of 27 different drones carried out those 59 flights over a period of four days. Of those, 25 flights exceeded 400’ above ground level (Transport Canada’s limit, except in special circumstances), with some flying more than 1500’ AGL. Eleven flights took place during hours of darkness at night – though that’s not a violation of regulations providing the drone is using lights that allow the pilot to maintain Visual Line of Sight and orientation.

While a number of those flights were likely curious hobbyists either ignorant of or willfully ignoring regulations, it’s believed at least some were likely piloted by protestors or supporters seeking to gain intelligence of police movements.

“The majority of those drones were not police or First Responder drones,” says Beaudette. “Some of them could have been looky-loos – just trying to see – or it could have been people wanting to know where the police were forming up.”

Drone flights, with identifying data redacted, via YOW

Restricted airspace

The airspace above Parliament Hill (as well as 24 Sussex Drive and Rideau Hall) is restricted to all aircraft – crewed and uncrewed – unless special authorization is obtained. In terms of drones, only law enforcement or other First Responders would have legal permission to fly except in special circumstances.

The data was obtained by Ottawa International Airport as part of a broader pilot project aimed at understanding drone traffic in proximity of the airport and developing protocols for aviation safety in the drone era. InDro Robotics is one of the partners in this project, providing key technology used in drone detection. Transport Canada regulations prohibit the operation of small RPAS within 5.6 kilometres of airports and 1.9 kilometres from helipads, except for pilots holding an advanced certification. Airspace permission is also required. (Drones weighing less than 250 grams are a different case, and we’ll touch on that shortly.)

How the drones were detected

The airport uses two different types of technology for drone detection. The first is a micro-Doppler Radar in conjunction with an automated camera. The system, called Obsidian, comes from the British firm QinetiQ. Its high frequency (9-12 GHz) radar can detect the spinning of propellers on a drone anywhere within a two-kilometre range of the airport. Once detected, a camera automatically zeros in on the drone.

You can get a good sense of how the system works via this QinetiQ video:

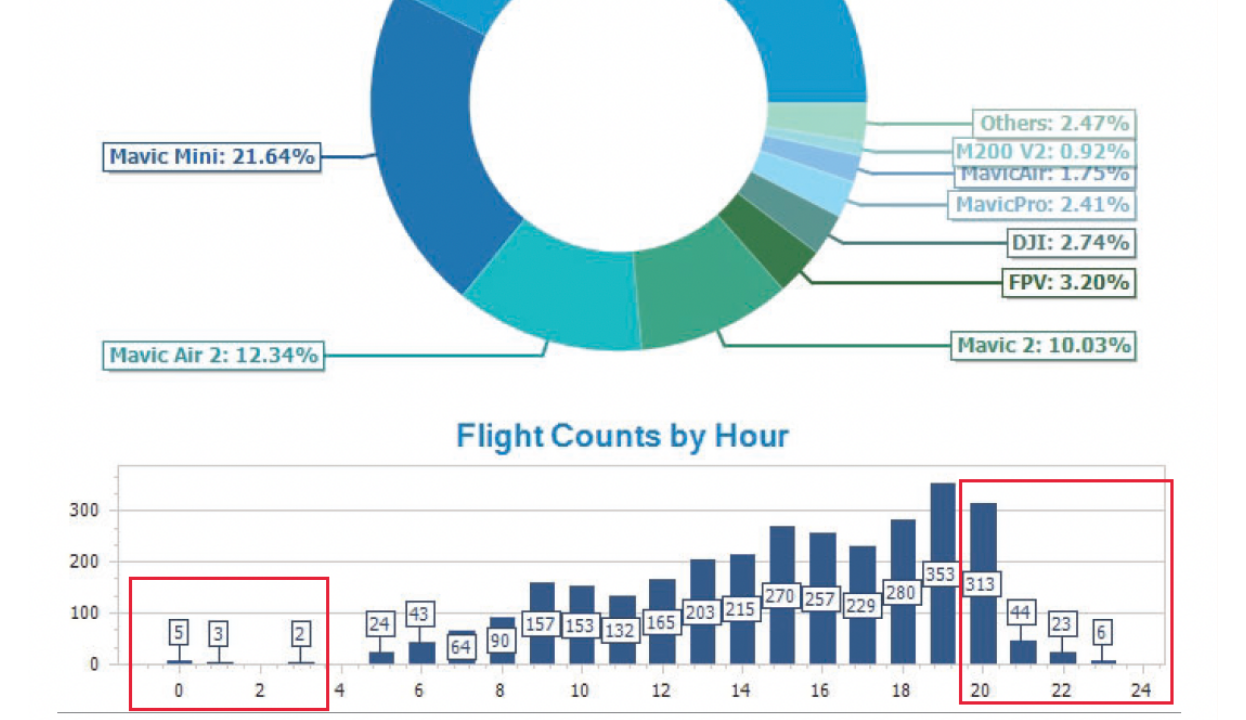

The second system has been supplied for the trials free of charge by InDro Robotics. It’s capable of capturing data from drones manufactured by DJI, which account for approximately 75 per cent of all consumer drones.

“Our system electronically ‘interrogates’ each device within its range,” explains InDro CEO Philip Reece. “We can triangulate the drone’s position – and on many models we’re able to also detect the type and serial number of the drone, its takeoff point, flight path, current GPS position and altitude. In addition, we can see where the pilot associated with that drone is located. With this data, YOW can quickly determine whether or not a given drone poses a threat to civil aviation.”

The system was intended to pick up any flights within a 15-kilometre radius of YOW. In practice, however, its range has been far greater.

“When we turned it on, we realized our expectations were far exceeded,” says YOW’s Michael Beaudette. “We were getting hits 40 kilometres plus. It’s really done the heavy lifting for the drone detection project. You can identify where the pilot is, where the drone is, and where they are in real time within 15 or 20 seconds.”

Data collected during the police operation to clear the protest reveals the bulk of the flights were carried out by DJI Mini 2 drones – very small machines that weigh just under 250 grams and which do not require a Transport Canada Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (RPAS) Certificate to operate. Microdrones like these are not prohibited from operation near airports or in controlled airspace if operated safely, but cannot gain access to the restricted airspace near Parliament without prior permission.

A controversial catalyst

So. What started this project?

The 2018 Gatwick Airport drone incident prompted many airports to take a closer look at the potential threat posed by drones. About 1000 flights were cancelled between December 19 and 21 following reports of two drones being sighted near the runway. Some 140,000 passengers were affected, with a huge economic impact.

The incident remains controversial, because there was never any clear physical evidence that drones had indeed posed a threat. Two people were wrongfully charged, released, and later received a settlement.

What cannot be denied, however, is that the highly disruptive incident was a massive wake-up call to airports worldwide. With an ever-growing number of drones in the air, the question of drone detection and potential mitigation became a pressing topic. If a drone detection system had been in place at Gatwick back then, it would have had concrete data as to whether there was truly a drone threat or not.

A Blue Ribbon Task Force was launched by the Association for Uncrewed Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) in conjunction with regulators and airport representatives. YOW President and CEO Mark Laroche was a member of the Task Force along with representatives of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and NAV Canada. (Its final report can be found here.)

Gatwick, then, was the catalyst that prompted YOW to start taking a very deep look at the issue.

Below: Gatwick Airport. Image by Mike McBey via Wikimedia Commons

“We wanted to be able to help shape a national drone response protocol for airports, so that we didn’t run into a situation like Gatwick, where we would have to shut down,” says Beaudette. “We didn’t even know if it’s a problem. We had to get some baseline data, some situational awareness. So we (decided to) focus on drone detection…to identify if it was even a threat.”

DJI, to its credit, has geofencing software that prevents its products from taking off in the immediate vicinity of major airports unless the pilot confirms on the app they have permission to do so. And while that’s useful, the geofencing is highly localized and cannot always prevent a pilot from putting a drone into the takeoff or landing path of an aircraft.

“What causes us concern is when they’re in the flight path,” says Beaudette.

In the fall of 2019, YOW began its pilot project. A news release made the project public in June of 2021, quoting Michael Beaudette as saying: “As an airport operator, we felt it was vitally important that we test systems to detect drones operating on flight paths, near the airport and in other restricted zones to help ensure the safety of air crews and passengers.”

Surprising data

With the InDro and QinetiQ systems up and running, the data started coming in. It was something of a shock.

“This opened our eyes,” says Beaudette. “We had no idea of the drone activity that was taking place.”

There were a lot of drone flights taking place close to YOW.

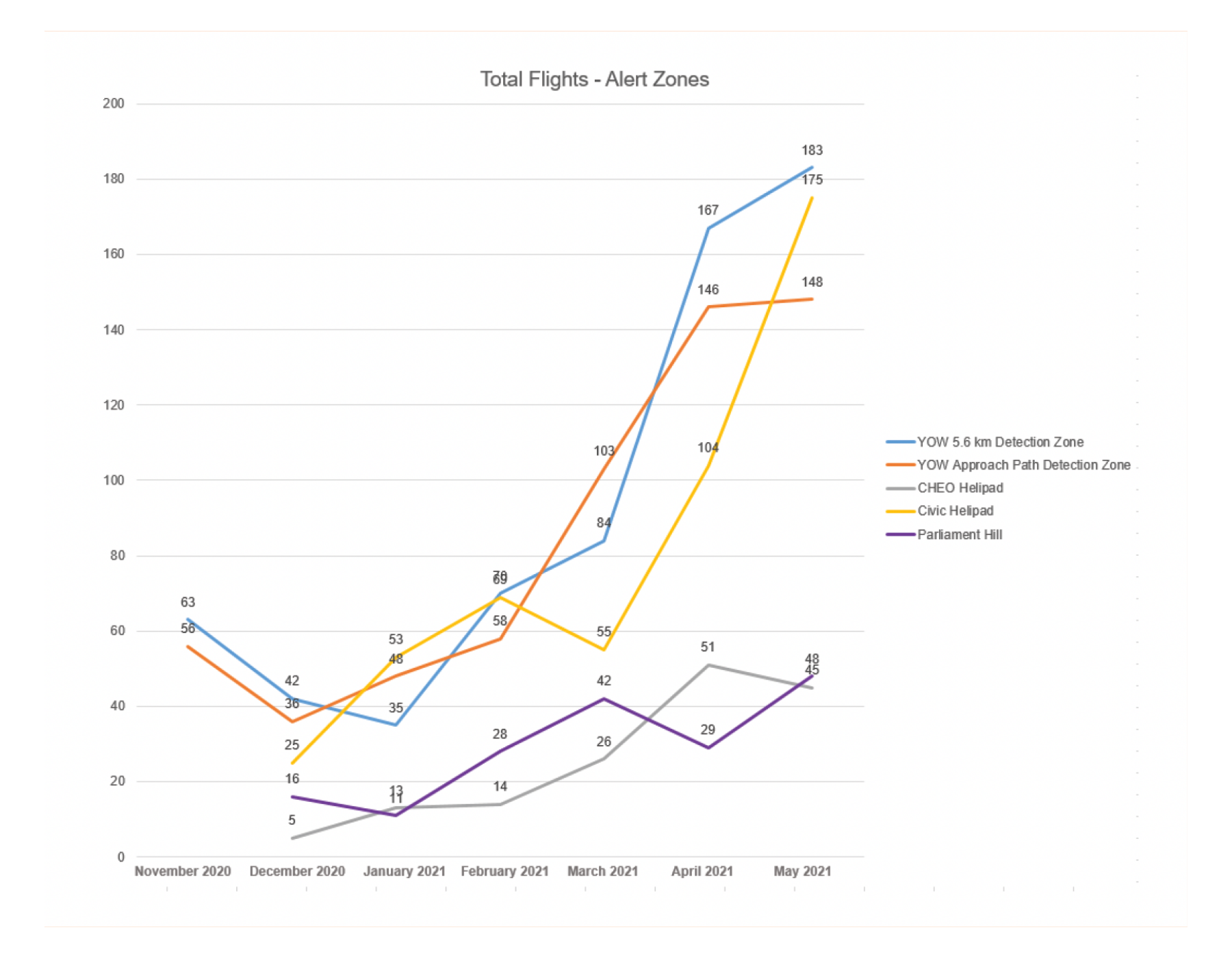

“In March of 2021, our program detected and reported on 101 drone flights within that 5.6-kilometre radius,” said CEO Mark Laroche in a news release. “April’s numbers were even higher at 167. A number of these were flown during hours of darkness and some exceeding altitudes of 1,600 feet.”

Every month, YOW crunches the data into a comprehensive report sent to Transport Canada, NAV Canada, InDro Robotics and other stakeholders. The report from May of 2021 reveals a steep increase in the number of flights.

The rapid increase was due to warmer weather and the increasing popularity of sub-250 gram drones, which are both more affordable and do not require an RPAS Certificate or registration. Here’s a breakdown of the top 30 drone models detected within a 15-kilometre radius during that same month:

The monthly report from this period states: “Detecting and identifying ‘drones of concern’ operating in the vicinity of the Ottawa Airport remains one of our primary objectives. This month, there were 19 such drones of concern within the YOW 5.6 km zone. These include drones that flew during hours of darkness, or were over 250 grams and flew over 400 ft. Of these 19 flights, there were 11 unique Drone IDs.”

Because the system can capture drones from even farther afield, other interesting data has emerged during the course of the pilot project.

“We started tracking other locations – Parliament Hill, Gatineau Airport,” says Beaudette. “And we were very surprised to see drones flying at all hours of the day and night and at high altitudes.”

These weren’t just hobby flights. Unusual activity was detected around certain embassies in Ottawa, with the same drones making repeated trips. There were drones flying close to the CHEO and Civic hospital Helipads used by helicopters with the air ambulance service Ornge. There were drones apparently peering into high-rise windows, Peeping-Tom style, and others that appeared to be involved with offering intelligence to people carrying out Break & Enters. (Beaudette says police were notified in some of these instances.)

As part of the Pilot Project, YOW worked with its partners – including NAV Canada, Transport Canada and InDro Robotics – for some real-world exercises. One such test involved determining the accuracy of the detection system. A drone was flown (with all appropriate permissions) from the E.Y. Centre, a massive exhibition/convention facility very close to the airport. When the data captured by the detection system was overlaid with the actual flight log, they were identical. Not only that, but the YOW data precisely identified the location of the pilot.

“We could actually tell which stall in the parking lot (the pilot was standing in),” says Beaudette.

Mitigation

Detection is one thing, but drone mitigation is quite something else. There are systems capable of jamming the Command and Control signal between the drone and the controller (including systems from Bravo Zulu Secure – part of the InDro group of companies. Here’s a quick overview of how these systems work.

But such systems are not in cards for YOW or other airports in Canada. Quite simply, Transport Canada and Industry Canada (which regulates radio spectrum frequencies) prohibit them in this country except in extraordinary circumstances.

“First and foremost, a drone – like any other airplane – is considered an aircraft,” says Beaudette. “And so Transport Canada has restrictions: Nobody has the authority to interfere with the flight of that aircraft. So you won’t see airports with jammers or other kinetic solutions to that unless they have the proper authority.”

Plus, he emphasizes, the Drone Detection Pilot Project is focused on drone detection. It’s a data-gathering exercise to help formulate protocols, provide useful information for regulators, and alert airport authorities immediately if a drone poses a threat to a flight path. YOW is not the drone police; its primary interest is in ensuring the safety of aircraft using the facility.

“If we can detect something, we may be able to mitigate it by rerouting aircraft, delaying aircraft, or we can locate the pilot,” says Beaudette.

Thankfully, despite many flights violating the 5.6 kilometre radius, YOW has not encountered a drone that posed a serious threat since the program began. Should that occur, it does have protocols in place to ensure civil aviation safety. Plus, of course, Transport Canada has the option of imposing heavy fines on pilots who put aircraft at risk or are flying without a Remotely Piloted Aircraft Certificate. And with the detection system in place, locating an offending pilot would not be difficult.

Know the regs

Ultimately, the biggest piece of the puzzle is around education. Some pilots simply don’t know the rules and unwittingly violate them – an excuse that won’t help them much if facing a fine. YOW has found, for example, that pilots often fly from nearby neighborhoods or golf courses without realizing they’re impinging on that 5.6 kilometre zone.

There’s also the issue of confusion around piloting sub-250 gram drones. Because they do not require an RPAS certificate or registration, many believe the rules somehow don’t apply to them. Yet the over-arching meaning of the regulations is clear: They must not be flown in an unsafe manner. And that includes near airports.

“We actually had a case where we found a drone that crash-landed inside the (airport) fence,” says Beaudette.

“We’re still the proud owners of that drone.”

InDro’s take

Several members of the InDro Robotics team – including our CEO – have expertise as private and commercial pilots. As a result, we have perhaps a heightened awareness of the potential risk drones can cause if they’re in the wrong place at the wrong time. Drone detection at airports and other sensitive facilities is critical, and the deep data collected by YOW reflects that.

We’re proud to be part of the YOW Drone Detection Pilot Project and look forward to assisting others with drone detection and even mitigation, where appropriate. If you’re interested in exploring such a system, we’d be happy to help.